El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

Background

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, “The Royal Road of the Interior Land,” was a rugged, often dangerous route running 1,600 miles from Mexico City to the royal Spanish town of Santa Fe from 1598 – 1882. During its first two centuries, El Camino Real brought settlers, goods and information to the province and carried its crops, livestock and crafts to the markets of greater Mexico. When Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, its northern frontier was opened to foreign trade, and New Mexico soon became the destination of a steady stream of traders carrying goods along the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri. El Camino Real connected with the Santa Fe Trail at Santa Fe and became the essential link between the growing U.S. economy and the long-established Mexican economy for the next 60 years.

This ancient road transcends time and place for its contribution to the history of two nations, with Indian, Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-American cultures each leaving their influence. Historic, ethnic, and cultural traditions were transmitted through El Camino Real. Aside from Western Civilization’s cultural values, a significant Hispanic culture survives today in the form of music, folktales, folk medicine, folk sayings, architecture, geographic place names, language, Catholic Religion, irrigation systems, and Spanish laws. Among the many food exchanges along the Camino Real was the red chile pepper, introduced into New Mexico by Spanish settlers from Mexico. The apple and other fruits were also introduced by settlers. Cattle, oxen, horses, mules, sheep, and goats – not to mention cats and dogs – were taken north to the New Mexican settlements.

Among the legal concepts presently utilized in the American legal system transmitted through El Camino Real are community property laws, land grant administration, first-priority in terms of water usage, mining claims, and the idea of sovereignty especially as applied to Native American land claims.

Description

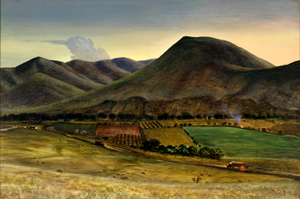

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro consisted of several extensive sections along with a number of parajes, a Spanish term referring to a camping place where travelers customarily stopped for the night. A paraje can be a town, a village, a pueblo, or simply a good location for stopping. Paraje typically are spaced 10 to 15 miles apart and feature abundant water and fodder for the traveler’s animals. A jornada is an arduous trail between two parajes that must be traveled in one day’s time because of lack of a water supply. One notable paraje on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro is El Rancho de las Golondrinas in La Cienega located between the Rio Grande and Santa Fe. Fort Craig and Fort Selden were also located along the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro consisted of several extensive sections along with a number of parajes, a Spanish term referring to a camping place where travelers customarily stopped for the night. A paraje can be a town, a village, a pueblo, or simply a good location for stopping. Paraje typically are spaced 10 to 15 miles apart and feature abundant water and fodder for the traveler’s animals. A jornada is an arduous trail between two parajes that must be traveled in one day’s time because of lack of a water supply. One notable paraje on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro is El Rancho de las Golondrinas in La Cienega located between the Rio Grande and Santa Fe. Fort Craig and Fort Selden were also located along the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

The first leg of El Camino Real was the route of Hernando Cortez, conqueror of the Aztec empire in 1521, who landed at the Mexican port city of Veracruz, connecting Spain to the new world, and marched his troops to Mexico City.

When silver was discovered in the mountains of Zacatecas, the heavily traveled road from Mexico City to the silver mines at Zacatecas, what originally had been an Aztec foot trail, became the second leg of El Camino Real.

The Rio Grande Pueblo Indian Trail, an ancient trade route that supplied Southwestern Indians with important trade goods, became the third leg or upper part of the Camino Real. Juan de Onate received permission from the King of Spain to conduct the first colonization expedition into the interior of what is today New Mexico using the Mexico City to Zacatecas trail and on to the Rio Grande Pueblo Indian Trail.

At this time explorers funded their own expeditions. The crown did not supply money, troops, colonists, or equipment. The only thing the Spanish crown supplied was its permission to go forth and risk one’s life and fortune. On January 26, 1598 Onate’s expedition enlisted 170 families and 230 single men to join his expedition. In addition 500 soldiers joined the ranks. Onate also included the Catholic Church in his expedition by recruiting the Franciscan priest Fray Rodrigo Duran who brought several other Franciscan priests with him. Five thousand head of livestock rounded out the future colonists’ holdings.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro represented the longest trade route in North America and a significant trail for the settlement of the Southwest. Onate established the settlement at San Gabriel. A few years later, Don Pedro de Peralta moved the small colony of San Gabriel to the newly founded town of La Ciudad de Santa Fe de San Francisco (City of the Holy Faith of St. Francis), which then became the trail’s terminus.

The Jornada del Muerto was one of the most feared sections along El Camino Real. It was a dreaded 90-mile waterless shortcut bypassing the 120-mile long westward “bend” of the Rio Grande. Following the river in this region, it was also treacherous, with deep arroyos, canyons, and quick sand, slowing travel considerably. At 8-10 miles per day for a caravan, this shortcut saved several days on the trail. Many would cross the flat, dry desert passage in a forced march, traveling all day and all night to shorten the trip to three days. This short cut would often claim some of the draft animals for want of water, fulfilling its name “Journey of Death.” Occasional attacks from the Apaches was yet another hazard along the portion of the trail, making the Jornada del Muerto one of the most deadly stretches of El Camino Real.

The Jornada del Muerto was one of the most feared sections along El Camino Real. It was a dreaded 90-mile waterless shortcut bypassing the 120-mile long westward “bend” of the Rio Grande. Following the river in this region, it was also treacherous, with deep arroyos, canyons, and quick sand, slowing travel considerably. At 8-10 miles per day for a caravan, this shortcut saved several days on the trail. Many would cross the flat, dry desert passage in a forced march, traveling all day and all night to shorten the trip to three days. This short cut would often claim some of the draft animals for want of water, fulfilling its name “Journey of Death.” Occasional attacks from the Apaches was yet another hazard along the portion of the trail, making the Jornada del Muerto one of the most deadly stretches of El Camino Real.

There are numerous stories concerning how the Jornada del Muerto, got its name. Though often translated as “Journey of the Dead Man,” this is incorrect. The genesis of the name is well documented to the late 1600’s Governor of New Spain (New Mexico), Antonio de Otermin. In August 1680 the Pueblo Revolt forced retreat of the Spanish. Governor Otermin found 2,520 refugees congregated at Paraje Fra Cristobal. Most were suffering from exposure, starvation and sickness. Otermin had no choice except to order the continuation of the retreat to El Paso, 120 miles to the south, and the next inhabited settlement where they would find food and relief. On September 14, 1680, they entered the waterless desert passage for what turned into a grueling nine-day death march. Over 500 perished on the trail. Governor Otermin called it a “Journey of Death,” or in Spanish, Jornada del Muerto. The group arrived in El Paso with 1,946, a total loss of 574 souls.

In 1698, when the reoccupation of New Mexico began, the deadly march had become legend, and the name of the desert expanse, Jornada del Muerto, firmly christened. For over 300 years, this deadly portion of the trail lived up to its name.

In the later days of the trail, beginning in 1848, the U.S. Army built numerous forts to protect travelers along El Camino Real. Fort Craig was built in 1854, south of Socorro, to primarily protect travelers through the Jornada del Muerto. Fort Selden, north of Las Cruces, was added in 1864 near the San Diego river crossing and paraje. Both forts provided soldiers to escort caravans and travelers through the Jornada, and patrols looking for those in distress. Buffalo soldiers, the nickname given to the African American cavalry by the Native American tribes they fought, were often used for escort service through the Jornada del Muerto.

During colonial times, La Bajada Hill was the dividing line between the two great economic and governmental regions of Hispanic New Mexico: the Rio Abajo (lower river district) and the Rio Arriba (upper river district). The large sprawling mesa on whose edge La Bajada is located is called La Mojada, “sheepfold”, or “place where shepherds keep their flocks”, but because the road from Santa Fe to the Rio Abajo descended from the mesa here, the escarpment took the name La Bajada, “the descent.” At this point in their journey, travelers on El Camino Real could choose one of three ways to reach Santa Fe: (1) La Bajada Hill was the most difficult; (2) the Santa Fe River Canyon (La Boca) was the most often selected; and (3) traveling Galisteo Creek, over the escarpment in the Luna Lopez Grant.

During colonial times, La Bajada Hill was the dividing line between the two great economic and governmental regions of Hispanic New Mexico: the Rio Abajo (lower river district) and the Rio Arriba (upper river district). The large sprawling mesa on whose edge La Bajada is located is called La Mojada, “sheepfold”, or “place where shepherds keep their flocks”, but because the road from Santa Fe to the Rio Abajo descended from the mesa here, the escarpment took the name La Bajada, “the descent.” At this point in their journey, travelers on El Camino Real could choose one of three ways to reach Santa Fe: (1) La Bajada Hill was the most difficult; (2) the Santa Fe River Canyon (La Boca) was the most often selected; and (3) traveling Galisteo Creek, over the escarpment in the Luna Lopez Grant.

Later History

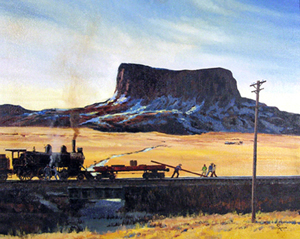

Historians give the date 1885 as the death of El Camino Real, when the railroad effectively made the trail obsolete. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad closely follows El Camino Real including through the Jornada del Muerto.

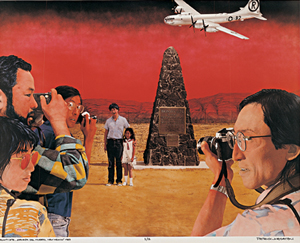

In 1945, the U.S. Army chose the desolate Jornada del Muerto to detonate the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site. The North American Trade Agreement became fully implemented on January 1, 2008. There are four corridors established in the agreement one of which is the Central Western corridor. It has the second largest trade volume of all the North American corridors. The route links Chihuahua in Mexico to Denver, Colorado, via the Paso del Norte, the ports of entry of El Paso/Ciudad Juarez between Chihuahua and Texas, and Santa Teresa in New Mexico.

In 1945, the U.S. Army chose the desolate Jornada del Muerto to detonate the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site. The North American Trade Agreement became fully implemented on January 1, 2008. There are four corridors established in the agreement one of which is the Central Western corridor. It has the second largest trade volume of all the North American corridors. The route links Chihuahua in Mexico to Denver, Colorado, via the Paso del Norte, the ports of entry of El Paso/Ciudad Juarez between Chihuahua and Texas, and Santa Teresa in New Mexico.

El Camino Real remains alive and well. Today Interstate I-25 serves the same purpose as the original trail, following the historic route along the west side of the Rio Grande quite closely. The 400 mile route within the United States was designated a National Historic Trail on October 3, 2000 and is currently overseen by both the National Park Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Today the Jornada del Muerto contains some of the best-preserved sections of El Camino Real.

The El Camino Real International Heritage Center is one of New Mexico's newest State Monuments, dedicated in November 2005. The Center contains award winning exhibits, an interpretive learning center, and artifacts presenting the history and heritage of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro—The Royal Road to the Interior.

Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail got its start in 1821, with an advertisement in the "Missouri Intelligencer" by Captain William Becknell, seeking men willing to join and invest in a trading expedition to the west. With the team he organized, Becknell headed his mules west from Franklin, Missouri in September 1821, loaded with goods he planned to take through what is now Kansasto the then, Mexican city of Santa Fe. He arrived in November, and though along and arduous trip, trading was good. Becknell returned home with money inhis pockets and exciting tales of his travels.

The Santa Fe Trail got its start in 1821, with an advertisement in the "Missouri Intelligencer" by Captain William Becknell, seeking men willing to join and invest in a trading expedition to the west. With the team he organized, Becknell headed his mules west from Franklin, Missouri in September 1821, loaded with goods he planned to take through what is now Kansasto the then, Mexican city of Santa Fe. He arrived in November, and though along and arduous trip, trading was good. Becknell returned home with money inhis pockets and exciting tales of his travels.

From 1821 to 1846, as more and more traders took their goods over the Santa Fe Trail, it became an international commercial highway used by Mexican and American traders. The 900-mile trail connected Old Franklin, Missouri to Santa Fe and was the lifeline linking the New Mexico Territory to the eastern United States.

With the start of the Mexican-American War in 1846, the Army of the West followed the Santa Fe Trail to invade New Mexico. When the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in1848, the Santa Fe Trail became a national road connecting the United States to the new southwest territories.

Trail trade and military freighting boomed. Commercial freighting along the trail included considerable military freight hauling to supply the southwestern forts. Military forts along the Trail provided the backing and support of the US Government, and subdued and relocated the native peoples of the Plains and the Southwest. Great caravans of freight wagons loaded with trade goods generated $5 million in 1855, and by 1866 over 5,000 wagons carried $40 million worth of goods. Stage coachlines, gold seekers heading to the California and Colorado gold fields, adventurers, fur trappers, and emigrants all used the Trail.

Trade also created opportunities for individual entrepreneurs. New Mexican saloon owner Dona Gertrudis "LaTula" Barcelo invested in trade. Wyandotte Chief William Walter leased a warehouse in Independence, Missouri, and his tribe invested in the trade. Hiram Young bought his freedomfrom slavery and became a wealthy maker of trade wagons – and one of thelargest employers in Independence. Blacksmiths, hotel owners, arrieros (muleteers), lawyers, and many others found their places along the Trail. Trade flourished.

Bythe 1870s the barons of commerce turned their eyes to the railroads. With the expansion of railroads acrossthe continent, freighters and stagecoaches began to disappear. In 1879, utilizing part of the old Santa Fe Trail, the first Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad crossed Raton Pass and headed toward Santa Fe making the Santa Fe Trail a thing of the past. By1880 newspaper headlines declared, "The Santa Fe Trail Passes into Oblivion."

Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (often abbreviated as Santa Fe) had its humble beginnings in 1860, originally organized to connect Atchison and Topeka, Kansas with Santa Fe, New Mexico. The originator of the enterprise was Colonel Cyrus K. Holliday of Kansas, one of the founders of Topeka, and a long time resident of that city. Colonel Holliday drew up the charter of the company and as a member of the territorial senate of 1859 secured its passage.

The Santa Fe's first tracks reached the Kansas/Colorado state line in 1873, and connected to Pueblo, Colorado in 1876. Although the railway was named in part for the capital of New Mexico, its main line never reached there as the terrain made it too difficult to lay the necessary tracks. The city of Santa Fe was ultimately served by a branch line from the small town of Lamy, several miles out of town. In order to help fuel the railroad's profitability, the Santa Fe set up real estate offices and sold farmland from the land grants that the railroad was awarded by the United States Congress. These new farms would create a demand for transportation, both freight and passenger service, that was offered by the Santa Fe. The Santa Fe played a key role in promoting the art and culture of the Southwest people and their “Enchanted Land,” creating a “romantic” vision of the Southwest, stimulating travel to the area.

The Santa Fe's first tracks reached the Kansas/Colorado state line in 1873, and connected to Pueblo, Colorado in 1876. Although the railway was named in part for the capital of New Mexico, its main line never reached there as the terrain made it too difficult to lay the necessary tracks. The city of Santa Fe was ultimately served by a branch line from the small town of Lamy, several miles out of town. In order to help fuel the railroad's profitability, the Santa Fe set up real estate offices and sold farmland from the land grants that the railroad was awarded by the United States Congress. These new farms would create a demand for transportation, both freight and passenger service, that was offered by the Santa Fe. The Santa Fe played a key role in promoting the art and culture of the Southwest people and their “Enchanted Land,” creating a “romantic” vision of the Southwest, stimulating travel to the area.

Santa Fe passenger service, which continued until 1971, when Amtrak took over passenger service, set the standard for luxury and attention to detail, with famed trains like the Super Chief, the El Capitan, the Valley Flyer,and the Texas Chief. In association with this legendary passenger service, Fred Harvey was the first to establish a chain of restaurants, hotels, lunch counters and dining rooms to feed and accommodate millions of travelers, and in the late 19th century the Fred Harvey Company became a leader in promoting tourism in the American Southwest. The company and its employees, including the famous waitresses who came to be known as "Harvey Girls", successfully brought higher standards of both civility and dining to a region widely regarded in the era as "the Wild West". Several Harvey Houses are still operating today.

At its largest the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway would own well over 13,000 miles and the routes which made up its system would become some of the most heavily and strategically used throughout the West that remains so to this day. Even before the intermodal revolution the Santa Fe's system was key to allowing the fast movement of goods in transit from Chicago and other gateway cities to the west coast, and vice versa. Coupled with this business the Santa Fe also served a number of manufacturing centers throughout the south and southwest.

Much of the railroad’s success throughout its existence was a result of its willingness to embrace new technologies and strive for excellence. Several “firsts” the railroad is credited with include autoracks, a term describing a railroad car built specifically with two or three levels to haul automobiles, and the innovative TOFC (trailer-on-flat-car) or piggyback service.

The mid-1990s would finally see this famous railroad’s name come to an end as it agreed in 1994 to merge with northwestern giant, Burlington Northern, to form the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, who recently changed its name to simply the BNSF Railway. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and its famous Warbonnet livery is gone, but its legend will live on in the songs and films and model trains it inspired.

Route 66

Although entrepreneurs Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and John Woodruff of Springfield, Missouri deserve most of the credit for promoting the idea of an interregional link between Chicago and Los Angeles, their lobbying efforts were not realized until their dreams merged with the national program of highway and road development.

While legislation for public highways first appeared in 1916, with revisions in 1921, it was not until Congress enacted an even more comprehensive version of the act in 1925 that the government executed its plan for national highway construction. Officially, the numerical designation "66" was assigned to the Chicago-to-Los Angeles route in the summer of 1926. With that designation came acknowledgment as one of the nation's principal east-west arteries. From the outset, public road planners intended U.S. 66 to connect the main streets of rural and urban communities along its course for the most practical of reasons: most small towns had no prior access to a major national thoroughfare.

Route 66 was a highway spawned by the demands of a rapidly changing America. Its diagonal course linked hundreds of predominantly rural communities in Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas to Chicago; thus enabling farmers to transport grain and produce for redistribution. The diagonal configuration of Route 66 was particularly significant to the trucking industry, which by 1930 had come to rival the railroad for preeminence in the American shipping industry. The abbreviated route between Chicago and the Pacific coast traversed essentially flat prairie lands and enjoyed a more temperate climate than northern highways, which made it especially appealing to truckers.

In his famous social commentary, The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck proclaimed U.S. Highway 66 the "Mother Road." Steinbeck's classic 1939 novel, combined with the 1940 film recreation of the epic odyssey, served to immortalize Route 66 in the American consciousness. An estimated 210,000 people migrated to California to escape the despair of the Dust Bowl. In the minds of those who endured that particularly painful experience, and in the view of generations of children to whom they recounted their story, Route 66 symbolized the "road to opportunity." From 1933 to 1938 thousands of unemployed male youths from virtually every state were put to work as laborers on road gangs to pave the final stretches of the road. As a result of this monumental effort, the Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway was reported as "continuously paved" in 1938. Route 66 symbolized the renewed spirit of optimism that pervaded the country after economic catastrophe and global war. Often called, "The Main Street of America", it linked a remote and under-populated region with two vital 20th century cities – Chicago and Los Angeles.

In his famous social commentary, The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck proclaimed U.S. Highway 66 the "Mother Road." Steinbeck's classic 1939 novel, combined with the 1940 film recreation of the epic odyssey, served to immortalize Route 66 in the American consciousness. An estimated 210,000 people migrated to California to escape the despair of the Dust Bowl. In the minds of those who endured that particularly painful experience, and in the view of generations of children to whom they recounted their story, Route 66 symbolized the "road to opportunity." From 1933 to 1938 thousands of unemployed male youths from virtually every state were put to work as laborers on road gangs to pave the final stretches of the road. As a result of this monumental effort, the Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway was reported as "continuously paved" in 1938. Route 66 symbolized the renewed spirit of optimism that pervaded the country after economic catastrophe and global war. Often called, "The Main Street of America", it linked a remote and under-populated region with two vital 20th century cities – Chicago and Los Angeles.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which provided a comprehensive financial umbrella to underwrite the cost of the national interstate and defense highway system, began construction of a modern four-lane highway which by 1970 bypassed nearly all segments of the original Route 66. The outdated, poorly maintained vestiges of U.S. Highway 66 completely succumbed to the interstate system in October 1984 when the final section of the original road was bypassed by Interstate 40 at Williams, Arizona.

Route 66 and New Mexico: Past and Present

Route 66 was first laid out in 1926. Back then it followed the Old Pecos Trail from Santa Rosa through Dilia, Romeroville, and Pecos to Santa Fe. From Santa Fe it went over La Bajada Hill and down to Albuquerque.

Route 66 was first laid out in 1926. Back then it followed the Old Pecos Trail from Santa Rosa through Dilia, Romeroville, and Pecos to Santa Fe. From Santa Fe it went over La Bajada Hill and down to Albuquerque.

In 1937 the New Mexico section of the highway was shortened by 107 miles. This more-direct route bypassed Santa Fe. By the end of 1937, the paving of Route 66 throughout the entire State was complete, making Route 66 New Mexico’s first fully paved highway. This is the route that would be followed by the new Interstate years later.

Today there are over 260 miles of pre-interstate era Route 66 that remains drivable. In a few places, the old road is still designated as state highway, although none continue to carry the U.S. 66 designation. Other portions have reverted back to county or tribal maintenance. The remaining miles have long since been "covered over" with super highway I-40.

To further the preservation of the Mother Road and the many historic landmarks along the old sections of the highway, New Mexico established those original roads still open to traffic as a National Scenic Byway in 1994. Starting at the New Mexico/Texas State Line, the byway travels 300 miles through compelling, scenic, and dramatic stretches of the famed highway.

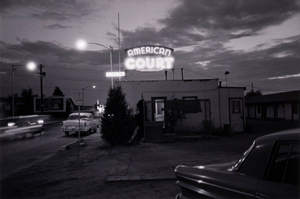

Another major undertaking in New Mexico was the Route 66 Neon Sign Restoration project by the New Mexico Route 66 Association. The Association led a tremendous effort along Route 66, restoring vintage neon signs in Tucumcari, Santa Rosa, Moriorty, Albuquerque, Grants, and Gallup. As a result, business owners, as well as entire communities, have a renewed pride in their Mother Road heritage.

Another major undertaking in New Mexico was the Route 66 Neon Sign Restoration project by the New Mexico Route 66 Association. The Association led a tremendous effort along Route 66, restoring vintage neon signs in Tucumcari, Santa Rosa, Moriorty, Albuquerque, Grants, and Gallup. As a result, business owners, as well as entire communities, have a renewed pride in their Mother Road heritage.