Minerals are the state’s richest natural resource, and New Mexico is one of the U.S. leaders in output of uranium and potassium salts. Petroleum, natural gas, coal, copper, gold, silver, zinc, lead, and molybdenum also contribute heavily to the state’s income.

Coal production

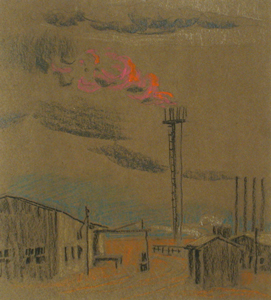

Coal production has played a significant role in the economic development of New Mexico beginning in the 1850’s and continuing to the present. It is one of the four mineral fuels produced in New Mexico, ranking third in value behind natural gas, (including coalbed methane) and crude oil. Coal resources underlie 12% (14.6 million acres) of the state’s total area. Most of the coal is in northern New Mexico, primarily in the San Juan and Raton basins. Several minor coal fields outside these basins have had significant production in the past, and some may become important in the future, in particular for coalbed methane production. Today, 46% of the state’s total energy needs are met through power generated from coal.

Coal is an important contribution to New Mexico’s state budget; it is the third largest source of revenues from mineral and energy production. Tax revenues (severance, resources excise, and conservation taxes, and royalties) from coal on state land were $30.7 million in 2001. New Mexico also receives 50% of the royalties collected on federal lands totaling $12.3 million in 2001. The coal industry directly employed 1,800 people in 2001 adding to the general economy of the State. Presently there are five operating coal mines in New Mexico, four surface and one underground operation. These mines produced 30.53 million tons in 2001, making New Mexico 12th in the nation for coal production.

Coal is an important contribution to New Mexico’s state budget; it is the third largest source of revenues from mineral and energy production. Tax revenues (severance, resources excise, and conservation taxes, and royalties) from coal on state land were $30.7 million in 2001. New Mexico also receives 50% of the royalties collected on federal lands totaling $12.3 million in 2001. The coal industry directly employed 1,800 people in 2001 adding to the general economy of the State. Presently there are five operating coal mines in New Mexico, four surface and one underground operation. These mines produced 30.53 million tons in 2001, making New Mexico 12th in the nation for coal production.

Acknowledgment

New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology (NM Tech)

Oil and Gas Production

Although traces of oil and natural gas in New Mexico date back to the late 1800’s, the first successful gas well wasn’t completed until 1921, nine years after New Mexico gained its statehood. A year later, New Mexico’s first regular quantities of crude oil were produced in a well west of Farmington, New Mexico.

These firsts led to years of eager exploration for what became known as “black gold.” In 1924, Van S. Welch, Tom Flynn, and Martin Yates drilled the first commercial oil well in southeastern New Mexico. The State Land Office received its first royalty payment of $125 for oil produced on state land. This occasion marked the beginning of a fruitful industry for New Mexico, forever shaping our state’s future.

In November 1927, a successful well was established in Lea County, the location of New Mexico’s greatest oil and gas production. Two years later, the discovery of the world-famous Hobbs pool quickly earned New Mexico a place among the top ten oil producing states in the nation.

In the wake of the stock market crash of 1929, New Mexico oil and gas producers gathered on December 11th, to discuss industry issues and concerns. This marked the formation of the “New Mexico Oil Men’s Protective Association,” now known as the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association commonly referred to as NMOGA.

Despite the nation’s financial turmoil, New Mexico’s oil industry quickly grew and by 1932 major pipelines extended into Lea County, transporting oil to eastern markets. In the same year, New Mexico established six refineries manufacturing gasoline, kerosene, heating oil, and road oil—a key factor to the development of New Mexico’s first asphalt highways. The market value of oil and gas tripled between 1932 and 1942 and New Mexico’s oil and gas industry flourished. At this time, the New Mexico Oil Conservation Commission was established, pioneering the controlled production of oil and gas so as to prevent unnecessary waste. New Mexico’s stance helped the United States Congress form the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission, a government entity designed to regulate the nation’s petroleum production.

Despite the nation’s financial turmoil, New Mexico’s oil industry quickly grew and by 1932 major pipelines extended into Lea County, transporting oil to eastern markets. In the same year, New Mexico established six refineries manufacturing gasoline, kerosene, heating oil, and road oil—a key factor to the development of New Mexico’s first asphalt highways. The market value of oil and gas tripled between 1932 and 1942 and New Mexico’s oil and gas industry flourished. At this time, the New Mexico Oil Conservation Commission was established, pioneering the controlled production of oil and gas so as to prevent unnecessary waste. New Mexico’s stance helped the United States Congress form the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission, a government entity designed to regulate the nation’s petroleum production.

Between 1952 and 1962, additional pipelines were built stretching from the gas fields of northwestern New Mexico to west coast markets. With distribution channels coast-to-coast, New Mexico’s oil and gas industry thrived. Advances in technology further contributed to the industry’s growth as recovery methods such as steam injection and solvent displacement became widely used. In 1960 Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Kuwait formed OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, forever changing the face of the world’s petroleum industry.

The industry has, and continues to experience its share of booms and busts, economic highs and lows, and periods of growth and stagnation. Rolling with the punches, New Mexico has fared well. The state remains a top producer of oil and natural gas and in year 2000 produced approximately 10% of the nation’s gas supply and 65.4 million barrels of crude oil. New Mexico is the second largest in natural gas reserves in the lower forty-eight states. It is the sixth largest producer of crude oil in the lower forty-eight states and ranks fourth in crude oil reserves. With a history dating back to the state’s birth, New Mexico’s oil and gas industry enjoys a rich legacy of growth, shaping our past, our present, and our future.

Just how important is the oil and natural gas industry to the state of New Mexico? For decades, New Mexico’s oil and gas producers have played a huge role in the state’s economy. The industry provides New Mexico schools, roads and public facilities with more than $2.5 billion in funding each year. It is the state’s largest civilian employer. Each night 23,000 New Mexicans come home to their families from jobs related to the oil and gas industry.

It is the state’s leading educational supporter and provides over 90 percent of all school investment through the Permanent Fund. The oil and gas industry also makes up 15 to 20% of New Mexico’s General Fund revenues. These are distributed to public schools and state colleges, fund the construction of public roads, buildings and state parks, and help keep New Mexico’s government operational.

Ten of New Mexico’s counties currently produce oil and/or natural gas Chaves, Eddy, Lea, Roosevelt and Quay in the southeast, and McKinley, Rio Arriba, San Juan and Sandoval in the northwest and Colfax in the northeast. Pipeline mileage stretches more than 25,000 miles, exceeding the combined mileage of New Mexico’s railroads and highways. In year 2007, over 1200 new wells were drilled and the state produced 1.6 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 65.4 million barrels of crude oil.

While oil and gas activities are vital to New Mexico and to those counties in which the industry operates, it also affects the lives of people nationwide. Together, oil and natural gas supply 65% of the energy we use every day. The U.S. oil industry alone employs nearly 1.5 million people. Oil fuels our planes, trains, trucks and other automobiles, and natural gas is used to heat and cool. Toys, TV’s, aspirin, and even toothpaste are products of petroleum.

While oil and gas activities are vital to New Mexico and to those counties in which the industry operates, it also affects the lives of people nationwide. Together, oil and natural gas supply 65% of the energy we use every day. The U.S. oil industry alone employs nearly 1.5 million people. Oil fuels our planes, trains, trucks and other automobiles, and natural gas is used to heat and cool. Toys, TV’s, aspirin, and even toothpaste are products of petroleum.

Acknowledgment

New Mexico Oil & Gas Association

http://www.nmoga.org

Uranium Mining

New Mexico’s energy and mineral wealth is one of the richest endowments of any state in the United States. New Mexico has the second largest identified uranium ore reserves of any state after Wyoming, but no uranium ore has been mined in New Mexico since 1998. Uranium mining in New Mexico is not what one would consider a success story. In fact, is it fraught with corporate disregard for the land and the indigenous people who worked the mines early on.

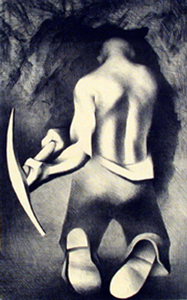

When Anglo-American miners appeared on the Colorado Plateau in the late nineteenth century, they extracted uranium, radium, and vanadium from small amounts of pitchblende and carnotite ore. Manual methods of mining, including the use of hand picks, sorting by hand, and transportation by burros or donkeys, limited the scope and impact of mining. During the early twentieth century, new mining methods included the use of diesel-powered equipment in underground mines and in transportation of ore by trucks to extraction mills. Thus began a dramatic increase in the impact of uranium mining on the areas resources.

The development of a boomtown economy from the 1940s through the 1960s on the Colorado Plateau coincided with federal government involvement in uranium mining providing financial incentives such as guaranteed ore prices, haulage and mine development allowances, production bonuses, fringe area and grade premium allowances. The 1950 discovery of uranium in the Grants, New Mexico area by a Navajo shepherd named Paddy Martinez, followed by the 1952 discovery of the MaVida Mine in Lisbon Valley prompted a well supported “uranium rush,” much of which occurred on reservation lands. The Navajo, Acoma, and Laguna tribes negotiated royalty agreements that required the use of local workers in mining operations, providing an economic boon after the devastating stock reductions during the 1930s.

Uranium mining operations were established on the Colorado Plateau in many locations, including some in Arizona (the Carrizo Mountains, the Lukachukai Mountains, Tuba City-Cameron area), in New Mexico (Churchrock-Crownpoint, the Ambrosia Lake and Jackpile districts on Mount Taylor), in Colorado (Naturita, Slick Rock, Durango, Grand Junction), and in Utah (Monument Valley, Moab, and Monticello).

Massive earth-moving equipment produced an exponential increase in the size of the mines and in the transportation network connecting mines to mills and markets. In the case of Anaconda’s New Mexico operations, a 65-mile railway link connected mine to mill. Depths of underground mines doubled or tripled, to 1000 feet, 1500 feet, and 2700 feet. The boom-time changed everything: size of the leases, depths of the mines, number of mill recovery facilities, and number of people involved in the industry, and the impact to the land and water resources.

Working conditions in the mines were abysmal by any standard. Miners, millers, truckers, and their families were exposed to radiation levels as much as 750 times the 1950 standards. By the 1950s, the first ghosts began to appear – ghosts of the victims of lung cancer, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, silicosis, tuberculosis, birth defects, and kidney damage. The Navajo called the ailments “red lungs” for the red they coughed up, or “uranium on the lungs” and “radiation around the heart.”

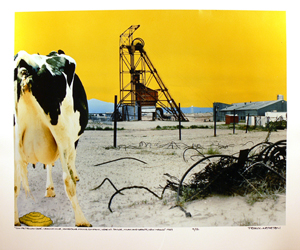

Leetso, the yellow monster, had released evil into Dine’tah. The industry went bust in the ‘80s, but the ghosts continue to congregate. A flood of eleven hundred tons of radioactive mill wastes and ninety million gallons of contaminated liquid poured down the Rio Puerco drainage at Church Rock, New Mexico, on July 16, 1979, thirty-four years to the day after Leetso’s birth.

The disaster at Church Rock was not an isolated event. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission acknowledges ten accidental releases of tailings (or uranium residue) solutions into major watercourses in the region between 1959 and 1977. Runoff of rainwater from tailings piles also contributes to the contamination of surface water. In 1984, a summer flash flood in Hack Canyon washed four tons of high-grade uranium ore into Kanab Creek and on to the Colorado River in Grand Canyon. In many communities, abandoned open pit uranium mines serve as stock tanks and swimming holes.

The mining and milling process greatly altered the land itself. The removal, transportation, and milling of vast quantities of rock resulted in the deposition of radioactive tailings piles at mine sites and at mill facilities. By 1978, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) recorded 140 million tons of on site tailings piles at twenty-two abandoned and sixteen operational mills. Continued production resulted in the addition of six to ten tons of tailings per year. One site, a 1.7 million-ton tailings pile, covers seventy-two acres in the center of Shiprock, New Mexico. Durango and Grand Junction, Colorado, and Monticello, Utah, are some of the other affected communities.

In 1992, the Navajo Nation president issued an executive order to reiterate the moratorium on uranium mining activity. Leetso, the yellow monster, is again raising his head. The world market for uranium is strong; the world’s reactors require 70,000 metric tons of U3O8; current world production is approximately 46,000 metric tons. An operation to mine uranium in situ by leaching with an alkaline solution has been proposed in the Crownpoint and Church Rock communities in New Mexico. Fears of groundwater contamination resulted in litigation by an association of community members to challenge the project’s operating license. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission requires that the mining company file an approved financial assurance plan to ensure cleanup of the mining site prior to commencing operation, which has effectively halted the project.

In 1992, the Navajo Nation president issued an executive order to reiterate the moratorium on uranium mining activity. Leetso, the yellow monster, is again raising his head. The world market for uranium is strong; the world’s reactors require 70,000 metric tons of U3O8; current world production is approximately 46,000 metric tons. An operation to mine uranium in situ by leaching with an alkaline solution has been proposed in the Crownpoint and Church Rock communities in New Mexico. Fears of groundwater contamination resulted in litigation by an association of community members to challenge the project’s operating license. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission requires that the mining company file an approved financial assurance plan to ensure cleanup of the mining site prior to commencing operation, which has effectively halted the project.

In 2003, Louisiana Energy Services (LES) proposed the National Enrichment Facility to be located near Eunice, New Mexico, in Lea County near the southeastern corner of the state. Uranium enrichment is a process by which natural uranium is separated into its component isotopes. Uranium-235, or enriched uranium, is used in fuel for nuclear reactors. The remaining uranium-238 is waste, and is also known as depleted uranium (DU).

The LES partnership is currently owned entirely by Urenco; previous partners dropped out following the issuance of the license to LES to construct and operate this facility. LES intends to use Urenco’s sixth generation gas centrifuge technology being used in Europe. Urenco has a capacity of about 20 percent of the world’s enrichment market.

Although the National Enrichment Facility has garnered extensive support, there remains serious concern regarding environmental, economic and political consequences.

Acknowledgments

Land Use History of North America: Colorado Plateau

MaryLynn Quartaroli

Northern Arizona University

http://cpluhna.nau.edu./Change/uranium.htm

United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission

Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety