Overview

Travelers have been coming to the Southwest, and New Mexico in particular, for many thousands of years. The earliest nomadic hunter-gatherers were seeking their subsistence until the Mogollon culture, in approximately 100 BC, settled in, building permanent pit houses and learning to farm. The Ancestral Pueblo people came next, with both these groups developing into the early Pueblo Culture.

It is interesting to note that in the first millennium, there are indications that transcontinental travel existed, as native people engaged in complex exchange networks trading both raw materials and finished artifacts over vast areas of North America. Obsidian, copper, pearls and other objects found in Ohio Valley Hopewell burial mounds provide evidence of materials that came from as far away as the Rocky Mountains, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Gulf of Mexico.

As the Pueblo culture was putting down roots, the Athabascans—the Navajo and Apache people—moved in from the north. These hunter-gatherers ultimately developed a long and productive relationship with their Pueblo neighbors.

The next and biggest wave of travelers were the Spanish explorers in the 1500’s who were in search of wealth and glory, and certainly power. On their heels were the Spanish clergy seeking to convert “the heathens” to Christianity, and as the Spanish military presence grew, settlers moved into the Nuevo Mexico region. In 1598 Don Juan de Oñate built the first permanent settlement in the American west; Don Pedro de Peralta founded Santa Fe as the first capital in 1610. Many decades passed with fighting and bloodshed the norm, but the Spanish settlers were determined and remained. Travel and trade between Mexico and Nuevo Mexico continued to expand, with trade fairs from Taos to El Paso common by the 1790’s.

Mountain men began arriving in Taos by 1750, and with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Taos became a base of operation and a refuge for these predominantly French-Canadian and American trappers and traders. Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821 dramatically changed the course of events in the New Mexico Territory. American traders were no longer outlawed, but were welcomed by the young Mexican government, hungry for the tariffs their merchandise would bring. The economy of New Mexico grew like wildfire.

From 1821 until the coming of the railroad in 1879, the Santa Fe Trail served as a vital commercial and military highway. The 900-mile trail connected Old Franklin, Missouri to Santa Fe and was the lifeline linking the New Mexico Territory to the Midwest and eastern United States. With Mexico’s independence from Spain, the Trail evolved into an international commercial highway used by Mexican and American traders.

The Trail provided a ready trade route for handmade indigenous goods from the New Mexico Territory to find their way into Victorian parlors and private collections back east. Traders, located at small posts in Hispanic villages, Navajo and Pueblo communities, accepted Native American  pottery and baskets, jewelry and weavings, and Spanish woodwork, weavings, and religious icons in exchange for the staples and manufactured goods they imported from the east. The traders then sold these objects to travelers and anthropologists as examples of a passing lifestyle, as the locals increased their dependence on manufactured products. Explaining this moment in the evolution of New Mexico’s economy, Joseph Traugott in How the West is One notes that, "the commodification of indigenous objects played a key role in New Mexico’s transition from a subsistence, agricultural economy to a money-based market economy." These trade items, representative of the indigenous culture of the Southwest, became an important factor in promoting tourism; they were not only useful as commodities for trade and art objects for collectors, but also as curios for travelers. Enterprising 19th century traders encouraged the indigenous people to make “tourist art”—smaller and cheaper mementos of their trip.

pottery and baskets, jewelry and weavings, and Spanish woodwork, weavings, and religious icons in exchange for the staples and manufactured goods they imported from the east. The traders then sold these objects to travelers and anthropologists as examples of a passing lifestyle, as the locals increased their dependence on manufactured products. Explaining this moment in the evolution of New Mexico’s economy, Joseph Traugott in How the West is One notes that, "the commodification of indigenous objects played a key role in New Mexico’s transition from a subsistence, agricultural economy to a money-based market economy." These trade items, representative of the indigenous culture of the Southwest, became an important factor in promoting tourism; they were not only useful as commodities for trade and art objects for collectors, but also as curios for travelers. Enterprising 19th century traders encouraged the indigenous people to make “tourist art”—smaller and cheaper mementos of their trip.

With the Louisiana Purchase, the ending of the Mexican-American War in 1848, and America's Civil War (1861–1865), the westward expansion of America would change this land forever. Empowered by the 19th century concepts of Manifest Destiny (the God-given directive for America to expand westward), and bearing the so-called “White Man’s Burden,” (the Christian moral obligation to convert and civilize Native peoples), European-Americans became the next tidal wave to journey to the Southwest.

The coming of the railroad to New Mexico in 1879 provided the easy access that was needed, opening full-scale trade and migration from the east and Midwest.

Beginnings of the Tourist Industry

The 1880’s saw extensive growth in the numbers of people traveling to the Southwest. New Mexico, its land and people, was a primary destination for:

- ranchers and homesteaders looking for cheap land to settle on,

- geological expeditions surveying the land,

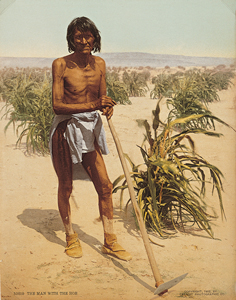

- ethnologists studying and documenting Native American lifestyles,

- businessmen looking for opportunities to sell or manufacture their goods,

- adventurers and gold prospectors,

- artists and photographers seeking inspiration, and

- lawyers and politicians hoping to provide a legal and political system for the lawless territory.

With the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad in 1879, people could travel to New Mexico in relative ease, compared to the rigors of the Santa Fe Trail. As life back east prospered, a whole new population of travelers came west. These were the “tourists,” people who had the time and means to take tours for recreational or leisure purposes—a radical change in the concept of travel. With this newest influx, the conscious development of tourism as an industry took hold.

Tourists were attracted to New Mexico for its great natural beauty. As images of the region appeared in magazines and journals, easterners were stunned by the huge spaces, deserts, canyons, and mountains. These views provided a remarkable contrast to the gentler, refined landscape, and built-up towns and cities where they lived. When artist Frederick Dellenbaugh, who accompanied Major John Wesley Powell’s western geological expeditions, exhibited his landscape paintings at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, spectators could not believe such a place actually existed!

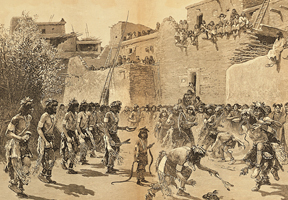

However, it was the exotic and romanticized images of Native American life that appeared in the pages of Harper’s and Scribner’s magazines that excited even greater interest—readers were fascinated with this vision of the Wild West and wanted to see it for themselves.

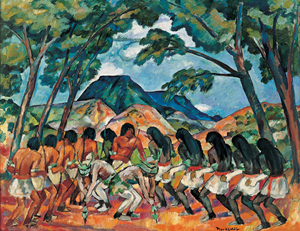

Artists flocked to New Mexico inspired by its vast natural beauty and the indigenous cultures that were so different from their own. Many of the early artists worked in a classical painting tradition that tended to romanticize native life. Not being ethnographers, they often created images mixing artifacts from their collections, thereby producing culturally inauthentic views of their subjects. These works were exhibited at galleries and expositions across the country, spreading a highly romantic, if not always accurate, vision of the Southwest.

Artists flocked to New Mexico inspired by its vast natural beauty and the indigenous cultures that were so different from their own. Many of the early artists worked in a classical painting tradition that tended to romanticize native life. Not being ethnographers, they often created images mixing artifacts from their collections, thereby producing culturally inauthentic views of their subjects. These works were exhibited at galleries and expositions across the country, spreading a highly romantic, if not always accurate, vision of the Southwest.

The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad realized the collective power of these images for promoting travel, and was quick to appropriate the romance of the west as part of their advertising campaign. How could the Santa Fe Railroad make the trip itself appealing? For the gentrified tourist, traveling in comfort was a new concept. Enter Fred Harvey, whose impact on tourism in New Mexico is legendary.

Fred Harvey was an innovative entrepreneur who understood the tourist’s needs, developing what became the first chain of restaurants across New Mexico and the west—The Harvey House— standardizing high quality food and service at railroad eating-houses. Later, at more prominent locations, these restaurants evolved into hotels, many of which survive today. By the late 1880s, there was a Fred Harvey dining facility located every 100 miles along the Santa Fe Line. Another innovation was his policy of hiring only female waitresses, the Harvey Girls, who were single, well-mannered, and educated "young women, 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent,” so his newspaper advertisement read.

Fred Harvey was an innovative entrepreneur who understood the tourist’s needs, developing what became the first chain of restaurants across New Mexico and the west—The Harvey House— standardizing high quality food and service at railroad eating-houses. Later, at more prominent locations, these restaurants evolved into hotels, many of which survive today. By the late 1880s, there was a Fred Harvey dining facility located every 100 miles along the Santa Fe Line. Another innovation was his policy of hiring only female waitresses, the Harvey Girls, who were single, well-mannered, and educated "young women, 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent,” so his newspaper advertisement read.

Harvey is known for pioneering the art of commercial cultural tourism. His "Indian Detours" were meant to provide an authentic Native American experience by having actors stage a certain lifestyle in the desert in order to sell tickets to unwitting tourists. He became a postcard publisher, both to promote business, and to serve as souvenirs. In 1902 at the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, Harvey built a museum and gift shop to show and sell Native American art, and even earlier began to commission Indian jewelry to sell at his outlets. Harvey’s daring vision helped to create New Mexico as a major tourist destination. His multi-generational family business essentially invented the hospitality industry, radically changing the way Americans traveled and spent their leisure time forever.

Harvey is known for pioneering the art of commercial cultural tourism. His "Indian Detours" were meant to provide an authentic Native American experience by having actors stage a certain lifestyle in the desert in order to sell tickets to unwitting tourists. He became a postcard publisher, both to promote business, and to serve as souvenirs. In 1902 at the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, Harvey built a museum and gift shop to show and sell Native American art, and even earlier began to commission Indian jewelry to sell at his outlets. Harvey’s daring vision helped to create New Mexico as a major tourist destination. His multi-generational family business essentially invented the hospitality industry, radically changing the way Americans traveled and spent their leisure time forever.

Acknowldegments

The Art of New Mexico: How the West is One

Joseph Traugott

Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, 2007

Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West

Stephen Fried

Bantam, 2010

Tourism and the Arts

Tourism and the arts go hand in hand in New Mexico, from the early days when tourism became a conscious industry, through to our own times.

In the late 19th century the two main ideas motivating artists to visit and work here were the concept of New Mexico as a picturesque locale with an exotic and colorful population, and counter to this view, the goal of preserving and documenting authentic lifestyles of the Native American and Hispanic communities. Both of these visions resulted in paintings and photography shown back east in galleries and museums, magazines and newspapers, souvenir postcards, and incorporated into calendars and advertising materials.

In the late 19th century the two main ideas motivating artists to visit and work here were the concept of New Mexico as a picturesque locale with an exotic and colorful population, and counter to this view, the goal of preserving and documenting authentic lifestyles of the Native American and Hispanic communities. Both of these visions resulted in paintings and photography shown back east in galleries and museums, magazines and newspapers, souvenir postcards, and incorporated into calendars and advertising materials.

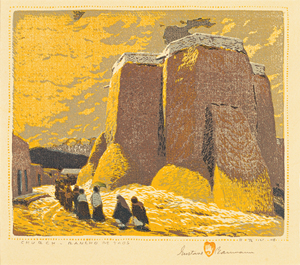

One early group of artists settled in Taos. Bert Geer Phillips had studied at the Julian Academy in Paris, where he met Ernest Blumenschein and Joseph Sharp. Their passionate interest in the landscape and people of the New Mexico pueblos inspired their fateful trip to the southwest in 1898. Outside of Taos, the wagon they were travelling in lost a wheel bringing them into the town where, inspired by the landscape, they decided to stop and paint. They became the only white artists operating in the region, displaying their work out of their studios, and becoming a major attraction for white tourists in Taos. The three artists helped found the Taos Society of Artists whose six original members, including E. Irving Couse, W. Herbert Dunton, and Oscar Berninghaus, tended to be European-trained illustrators and painters. By 1915, there were more than a hundred artists working in Taos, though only a handful were voted into the Taos society which finally disbanded in 1927, possibly due to decreased sales and publicity.

Classical European art, which had formed the foundation for most of the teaching that American artists experienced, had gone through a radical evolution. With the invention of the camera in the late 1800’s, adventurous artists in Europe felt liberated from the necessity to make representational art—the camera could do that! Instead, they began to experiment with artmaking itself as Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism and Cubism began to replace traditional picture making. In 1913, many American artists were treated to their first view of these new developments at the Armory for the Arts Exhibition in New York City where they saw the work of Cezanne and Matisse, Picasso and Duchamp, and a long list of other innovators. For some, it was considered a scandalous show, even an outrage. But for the history of American art, it was a watershed that introduced artists, collectors, art historians and the public accustomed to realistic art, to modern art. The show served as a catalyst for American artists, who became more independent and created their own "artistic language." New Mexico and its wide-open spaces offered an ideal place to explore, both in terms of subject matter and artistic style.

In the early years of the 20th century artists came to New Mexico in large numbers having been inspired by the early images, or having heard reports and seen the work of friends who had visited; some artists came for health issues finding the climate a respite for their tuberculosis. The coming of New Mexico Statehood in 1912 saw a rapid increase in the population.

Seventy miles south of Taos, a whole other arts community was rapidly developing. After the First World War, Santa Fe became what Joseph Traugott calls a “modernist destination,” as artists looking for fresh subject matter and a new approach in their painting came in droves. The modernist painters responded to the landscape and Native American and Hispanic life with more abstract, visually experimental paintings, which offered an opportunity for their own intellectual and emotional expression.

Another big draw for the modernists to Santa Fe was the opening in 1917 of the Museum of New Mexico Art Gallery (its name was changed to the Museum of Fine Arts in 1962). Edgar Hewett, an archeologist, educator, and administrator, was an instrumental figure in the development of the Museum and its first director. He understood the significance of the Museum and the arts for the economic development of the city and worked with local community leaders as well as state government to get the public and private funding that was needed to build a museum in a small town. Encouraged by Robert Henri, a well-known painter from New York City with a strong social conscience, Hewett developed the Museum’s Open-Door Policy, a non-exclusionary program which allowed any artist working in New Mexico to exhibit his or her work without the need for pre-approval by a jury. This radical democratic idea, closely allied to the progressive thinking of many younger Eastern artists, poets, and intellectuals, proved to be an enormous attraction.

Another big draw for the modernists to Santa Fe was the opening in 1917 of the Museum of New Mexico Art Gallery (its name was changed to the Museum of Fine Arts in 1962). Edgar Hewett, an archeologist, educator, and administrator, was an instrumental figure in the development of the Museum and its first director. He understood the significance of the Museum and the arts for the economic development of the city and worked with local community leaders as well as state government to get the public and private funding that was needed to build a museum in a small town. Encouraged by Robert Henri, a well-known painter from New York City with a strong social conscience, Hewett developed the Museum’s Open-Door Policy, a non-exclusionary program which allowed any artist working in New Mexico to exhibit his or her work without the need for pre-approval by a jury. This radical democratic idea, closely allied to the progressive thinking of many younger Eastern artists, poets, and intellectuals, proved to be an enormous attraction.

With a background in archaeology, Hewett also developed a program providing support for Pueblo artists like Maria Martinez, to work with historic clay and images, prompting a revival of pottery as a key ingredient in the economic development of Pueblo artists. The Museum’s open-door policy created a revolutionary model for exhibiting both indigenous Native American and Hispanic artists alongside the work of recognized New York painters and sculptors, making Santa Fe an ideal environment for the expansion of the arts for both economic development and as an attraction for tourists.

With a background in archaeology, Hewett also developed a program providing support for Pueblo artists like Maria Martinez, to work with historic clay and images, prompting a revival of pottery as a key ingredient in the economic development of Pueblo artists. The Museum’s open-door policy created a revolutionary model for exhibiting both indigenous Native American and Hispanic artists alongside the work of recognized New York painters and sculptors, making Santa Fe an ideal environment for the expansion of the arts for both economic development and as an attraction for tourists.

Many of the Modernist artists from New York joined forces in Santa Fe, just as the earlier artists did in Taos. Los Cinco Pintores consisted of Fremont Ellis, Jozeph Bakos, Walter Mruk, Will Shuster, and Willard Nash banding together in 1921 to experiment with modernist painting methods and leading colorful lifestyles. Another loose coalition called the New Mexico Painters formed in 1923 included Gustave Baumann, Ernest Blumenschein, and B.J.O. Norfeldt; their purpose, according to Time Magazine, November, 1923, was to hold annual exhibitions in New York, Chicago, and other art centers. For these artists, by the 1920’s the shift was from an ethnographic focus to painting itself. They were all interested in showing and selling their work.

As the arts community grew through the 1920’s, so did the conflicts around tourism—whether to maintain Santa Fe’s (and its indigenous and modernist) authenticity, or whether to cater to the tourist trade. Tourist revenues had become an essential component of the city’s income. In 1926 Route 66 wound its way through the state and car travel opened the floodgates—tourism expanded exponentially. A series of all-community events and festivals celebrating the city’s tri-cultural population provided an exciting destination for travelers interested in the arts and culture of the Southwest:

- The Santa Fe Fiesta, which had first taken place in 1712, was revived in 1919.

- The First Annual Exhibition of Indian Arts and Culture, took place in 1922, later evolving into the world-renowned Santa Fe Indian Market.

- In 1925, the Spanish Colonial Arts Society was founded and had its first Spanish Market in 1926.

- That same year artist Will Shuster moved his traditional burning of Old Man Gloom downtown behind City Hall, and the burning of Zozobra became an annual event.

.jpg) To provide a comfortable place for both in and out-of-state tourists to spend the night, La Fonda was remodeled in 1921. The Santa Fe Plaza became the hub of the city—the central place for locals and tourists to enjoy the city’s many cultural offerings.

To provide a comfortable place for both in and out-of-state tourists to spend the night, La Fonda was remodeled in 1921. The Santa Fe Plaza became the hub of the city—the central place for locals and tourists to enjoy the city’s many cultural offerings.

When the New York Stock Market Crash of 1929 put an abrupt stop to economic growth all across the country, the Southwest saw a sharp decline in tourism and the revenues the industry engendered.

Acknowldegement

The Art of New Mexico: How the West is One

Joseph Traugott

Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, 2007

Land of Enchantment

As Santa Fe and Taos were developing into arts destinations for travelers, other areas of New Mexico were being groomed for tourists interested in the natural wonders of the land. The year 1876 marked the grand centennial for the United States, and American nationalists seized upon the grand scenic vistas, particularly found in the American West, as a source of national pride. As the century neared its close, these "treasures" were increasingly included in national parks.

This national development had significant implications for tourism locally. The economic benefits to be derived from park status were not lost on early promoters. Parks brought visitors who would require a variety of services that translated into businesses and jobs. Following the Yellowstone Act, other park proposals proliferated as politicians sought a similar resource for their districts.

New Mexico’s own Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, played a monumental role in protecting not only the state’s, but the country’s natural resources. He aggressively promoted an expansion of federal public lands and assisted with the enactment of major environmental legislation. He oversaw the addition of four parks, six national monuments, eight seashores and lakeshores, nine recreation areas, 20 historic sites and 56 wildlife refuges to the National Park system. Udall’s work was central to the enactment of environmental laws such as the Clear Air, Water Quality and Clean Water Restoration Acts and Amendments, the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, the National Trail System Act of 1968, and Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968.

Chaco Canyon

In the middle of the 19th century, several of Chaco's major ruins were rediscovered. The first archaeological investigation commenced in May 1896, when the Hyde Exploring Expedition started work on Pueblo Bonito. This expedition launched over a century of archaeological excavations and surveys in the canyon and outlying areas and led to the creation of Chaco Canyon National Monument in 1907 under the auspices of the 1906 Antiquities Act.

Beginning in 1937 the Civilian Conservation Corps, part of the New Deal Work Relief Program, funded an experimental Mobile Unit to work on ruins salvage and stabilization, continuing to 1970. The crew was mostly Navajo, including one female member. Many members of the current preservation crew are second-generation Chaco stonemasons related to the original team. By 1959, the National Park Service had constructed a park visitor center, staff housing, and campgrounds.

Chaco was listed with the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and in 1980, the monument boundaries were expanded; the name was changed to Chaco Culture National Historical Park. The park received international attention when it was recognized as a World Heritage Cultural Park in 1987.

Acknowledgements

National Park Service

Chaco Culture, National Historic Park

http://www.nps.gov/archive/chcu/excavate.htm

Aztec Ruins

Aztec Ruins National Monument, bounded on the east by the Animas River, preserves an extensive community of multi-story structures, smaller residential buildings, roadways, ceremonial kivas, earthworks, and artifacts left by the 11th through 13th century ancestors of today’s Puebloans of the Southwest. The site was declared Aztec Ruin National Monument in 1923 and changed to Aztec Ruins in 1928. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and in 1987 was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites, as part of the Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

Acknowledgements

National Park Service

Aztec Ruins National Monument

http://www.nps.gov/azru/historyculture/index.htm

http://www.nps.gov/azru/naturescience/index.htm

Bandelier National Monument

Bandelier's human history extends back for over 10,000 years when nomadic hunter-gatherers followed migrating wildlife across the mesas and canyons. By 1150 CE Ancestral Pueblo people began to build more permanent settlements. By 1550 the Ancestral Pueblo people, formerly called the Anasazi, had moved from their homes on the mesas to pueblos along the Rio Grande (Cochiti, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Santo Domingo).

In the mid-1700's Spanish settlers with Spanish land grants made their homes in Frijoles Canyon. In 1880 Jose Montoya of Cochiti Pueblo brought Adolph F. A. Bandelier, an influential nineteenth century historian and anthropologist to the region, which became one of Bandelier’s favorite places for archaeological research. He went on to undertake pioneering ethnographic and archaeological research in the American Southwest and the central Andes, laying the foundation for anthropological research in these areas.

The establishment of the Bandelier National Monument in 1916 was a direct result of conflicting pressures on the limited space of the Pajarito Plateau. Archaeologists, homesteaders, stockmen, and the Santa Fe business community all had a stake in the region. Each group thought its use should take precedence and none retreated from its position. The intervention of Federal agencies only complicated an already volatile situation, and the eventual establishment of the monument was a compromise that was a prelude to further conflict. In 1916 legislation to create Bandelier National Monument was signed by President Woodrow Wilson. Between 1934 and 1941 workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) worked from a camp constructed in Frijoles Canyon. Among their accomplishments is the road into Frijoles Canyon, the current visitor center, a new lodge, and miles of trails. For several years during World War II the park was closed to the public and the Bandelier lodge was used to house Manhattan Project scientists and military personnel.

Today the National Park Service co-operates with surrounding pueblos, other federal agencies and state agencies to manage the park, which receives 300,000 visitors annually.

Acknowledgement

National Park Service

Bandelier National Monument

http://www.nps.gov/band/historyculture/index.htm

Gila Cliff Dwellings

The Mogollon once flourished in the Gila region leaving their imprint when they moved on, around 1300. By the time the first Spanish set foot in southwest New Mexico, the Mogollons and Mimbrenos had both disappeared, and Apaches, mostly Chiricahua, inhabited the area. Led by famous chiefs such as Cochise and Geronimo, the Apaches retreated to a remote stronghold, into the rugged forests and mountains of the wilderness. Because of their fierce protectiveness, the area remained undeveloped into the 1870s when the Apaches were squeezed out by Mexican and white settlers, ranchers, miners and prospectors.

The Mogollon once flourished in the Gila region leaving their imprint when they moved on, around 1300. By the time the first Spanish set foot in southwest New Mexico, the Mogollons and Mimbrenos had both disappeared, and Apaches, mostly Chiricahua, inhabited the area. Led by famous chiefs such as Cochise and Geronimo, the Apaches retreated to a remote stronghold, into the rugged forests and mountains of the wilderness. Because of their fierce protectiveness, the area remained undeveloped into the 1870s when the Apaches were squeezed out by Mexican and white settlers, ranchers, miners and prospectors.

In 1907 President Roosevelt, by executive proclamation, set aside a quarter section of land containing the "Gila Hot Springs Cliff-Houses" as Gila Cliff-Dwellings National Monument, specifically prohibiting settlement on the reservation and damage or appropriation of any of its features.

Aldo Leopold, a former Forest Service employee who devoted most of his adult life to preserving the nation's wild places, lobbied to have the Wilderness preserved by an administrative process of excluding roads and denying use permits. Through his efforts, this area became recognized in 1924 as the first wilderness area in the National Forest System. In 1964 President Lyndon B. Johnson enacted The Wilderness Act of 1964 designating certain Forest Service primitive areas as wilderness where humans are considered visitors, not residents of these areas, and machines are not allowed. Gila became the first congressionally designated wilderness area in the Wilderness Preservation system.

Acknowledgements

National Park Service

Gila Cliff Dwellings

http://www.nps.gov/archive/gicl/adhi/adhi.htm

Desert USA

http://www.desertusa.com/gila/gila.html

White Sands

A determined group of local promoters dreamed of attracting some kind of development to the Alamogordo area in order to capitalize on the dunes. Many proposals had been submitted regarding commercial development of the gypsum found in the dunes, but none had come to fruition. Seizing on the park idea, Tom Charles, one of the leaders suggested, "Gypsum may be divided into two classes - Commercial and Inspirational. The former everybody has, but as for recreational gypsum, we have it all. No place else in the world do you find these alabaster dunes with the beauty and splendor of the Great White Sands".

Charles' enthusiasm for the project was contagious and his perceptions about the value of the dunes also proved accurate. Interest in some sort of national recognition for the resource grew throughout the latter part of the 1920s. Studies were conducted by the National Park Service who determined that while the dunes might not meet the criteria for National Park status, which required a variety of resource values, the setting was ideal for preservation as a national monument. With the full backing of the New Mexico congressional delegation, as well as the support of communities from El Paso to Roswell, success was achieved.

Charles' enthusiasm for the project was contagious and his perceptions about the value of the dunes also proved accurate. Interest in some sort of national recognition for the resource grew throughout the latter part of the 1920s. Studies were conducted by the National Park Service who determined that while the dunes might not meet the criteria for National Park status, which required a variety of resource values, the setting was ideal for preservation as a national monument. With the full backing of the New Mexico congressional delegation, as well as the support of communities from El Paso to Roswell, success was achieved.

Formal recognition for the uniqueness of the white sands of southern New Mexico came in 1933, when President Herbert Hoover, acting under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906, proclaimed and established a White Sands National Monument.

In some ways the timing was fortuitous, for the establishment of the monument coincided with the dark days of the Depression and the economic recovery programs of the Roosevelt administration. WPA funds were used to improve many park areas and White Sands benefited by achieving a full measure of development within just a few years of opening. Construction projects included the visitor center/administrative building, maintenance facilities, public restrooms, and park residences. All of these buildings are still in service.

The park is currently examining its role as a laboratory for desert research and the potential for new programs in desert ecology. Its full moon evening guided walks are famous around the world. The park will also be looking for new ways to provide for visitor interaction with the desert’s resources.

Acknowledgement

National Park Service

White Sands National Monument

http://www.nps.gov/whsa/index.htm

Carlsbad Caverns

The park’s cultural resources represent a long and varied continuum of human use starting in prehistoric times, and illustrating many adaptations to the Chihuahuan Desert environment. Human activities, including prehistoric and historic American Indian occupations, European exploration and settlement, industrial exploitation, commercial and cavern accessibility development, and tourism have each left reminders of their presence, and each has contributed to the rich and diverse history of the area.

Carlsbad Cave National Monument was established in 1923 when the first photographs also appeared in the New York Times, stimulating interest in the cavern. Important events enhancing the rise of tourism were:

- From 1923 to 1927 the first trails, stairs and lights were installed, including a staircase from the natural entrance to Bat Cave.

- 1927. Cavern Supply Company was established as the park concessioner with an entry fee of $2.00 per person.

- 1928. Amelia Earhart visited the caverns.

- 1930. Congress designated the site as Carlsbad Caverns National Park.

- 1931. A 750' elevator shaft was drilled and blasted from both ends—the surface and the cavern, and the elevator was installed, going into operation in January 1932. (Two larger elevators and another shaft were added in the middle 1950s.)1937. The park received its 1 millionth visitor.

- 1938-1942. A Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp was established at Rattlesnake Springs to continue construction.1959. Construction of the current visitor center was completed; old stone buildings near the cave entrance were removed and tour operations transferred to the visitor center.

- 1967. Self-guided trips through the Big Room were begun, with Rangers stationed at points throughout the Big Room interpreting their section as visitors pass by.

- 1986. Lechuguilla Cave is discovered to go further than expected. Over the coming years, it was taken to over 110 miles of explored passageway.

- 1995. Carlsbad Caverns National Park was declared a World Heritage Site.

- 2005. A total of 39,000,000 tourists have visited the Monument.

Today, Carlsbad Cave National Monument receives more annual visitors than any other cultural resource in the state.

Acknowledgement

National Park Service

Carlsbad Caverns National Park

http://www.nps.gov/cave/historyculture/upload/history_site_bulletin.pdf

The Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge

The Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge was established under Franklin Roosevelt’s administration in 1939 "as a refuge and breeding grounds for migratory birds and other wildlife." The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, with the support of farmers and the Friends of the Bosque del Apache, have effectively re-established a wetlands environment, following the ecological wreckage caused by forest destruction, overgrazing, excessive hunting, river diversion and alien plant invasion. The Bosque del Apache has become an important environmental success story attracting thousands of birders and other eco-tourists each fall to watch the return of the Sandhill Cranes, Snow Geese, and other species wintering there.

Acknowledgements

US Fish and Wildlife Service

Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge

http://www.fws.gov/refuges/profiles/index.cfm?id=22520

Desert USA

Jay Sharp

http://www.desertusa.com/mag00/nov/stories/bosque.html

New Mexico’s Cities: Becoming Tourist Destinations

The arrival of the Model T Ford in1908 changed the face of America forever. As automobiles became accessible Americans began to travel further, and as travel increased, the public called for a standardized National Highway System. By 1926 a bill was signed in Washington D. C. and Route 66 became a reality. The 2,400-mile “Mother Road” connected small towns across the Midwest and West with the big cities of Los Angeles and Chicago. With road improvements and the advent of Interstate 40 and Interstate 25 later on, the ease of travel inaugurated a dramatic increase in tourism, with both small and large cities in New Mexico developing their unique tourist attractions.

Clovis

The city of Clovis, located in the Llano Estacado and largely an agricultural and ranching community, is also an important destination for tourists with two different interests.

Blackwater Draw was first recognized in 1929 as one of the most well-known and significant sites in North American archaeology. Early investigations at Blackwater Draw recovered evidence of human occupation in association with Late Pleistocene fauna, including Columbian mammoth, camel, horse, bison, sabertooth cat and dire wolf. Since its discovery, the site has been a focal point for scientific investigations by academic institutions and organizations from across the nation. The Blackwater Draw Museum first opened to the public in 1969 primarily to display artifacts describing and interpreting life at the site from Clovis times (over 13,000 years ago) through the recent historic period. Due to its tremendous long-term potential for additional research and to public interest, the site was incorporated into the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. More recently, it was declared a National Historic Landmark.

On a totally different note, Clovis describes itself at “the city built on Rock 'n' Roll.” Recently dubbed as New Mexico's 'best kept secret,' the Norman Petty 7th Street Studio is responsible for the "Clovis Sound," made popular by such greats as Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison who recorded at the studio. The original equipment is still in the studio. In 2007, the State of New Mexico recognized the studio with a NM Scenic Historic Marker, which is the first completed roadside marker commemorating Rock 'n' Roll culture that followed World War II. The Norman & Vi Petty Rock & Roll Museum honors Norman and Vi Petty and the artists who recorded at the 7th Street studio. A jukebox plays songs from the 50s and reminds visitors that Rock 'n' Roll is here to stay. The museum recreates a working recording studio from the 1950s and displays artifacts and memorabilia from the studios, including the original mixing board used by Norman Petty to record Buddy Holly and the Crickets. The annual Clovis Music Festival attracts hundreds of Rock 'n' Roll lovers.

Acknowledgements

Clovis Chamber of Commerce

http://www.clovisnm.org/

http://www.newmexicosouth.com/clovis/

Eastern New Mexico University

Blackwater Draw Museum

http://www.enmu.edu/services/museums/blackwater-draw/index.shtml

Las Cruces

Millions of years before the dinosaurs, Las Cruces teemed with reptiles and amphibians, whose stories are told in the endless scattering of fossils in nearby mountains and deserts. According to geologists, southern New Mexico was covered by a great inland sea 600 million years ago. When the sea retreated, many fossils were left behind.

The area where Las Cruces rose was first inhabited by the Mogollon People and later, the Apache. It was colonized by the Spanish beginning in 1598 when Juan de Oñate claimed all territory north of the Rio Grande for New Spain and later became the first governor of the Spanish territory of New Mexico. The area remained under New Spain control until 1821 when the First Mexican empire claimed ownership. The Republic of Texas also claimed the area during this time until the end of the Mexican American War in 1846-48. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 established the United States as owner of this territory and Las Cruces was founded in 1849 when the United States Army laid out the town plans. The first train reached Las Cruces in 1881, but not being a terminus or a crossroads, the population only grew to 2,300 in the 1880s. Las Cruces was incorporated as a town in 1907.

Las Cruces has become the economic and geographic center of the fertile Mesilla Valley, the agricultural region on the flood plain of the Rio Grande extending from Hatch, NM, to the west side of El Paso, TX. The growth of Las Cruces has been attributed to the university, government jobs and recently retirees. New Mexico State University was founded in 1888, New Mexico's only land-grant institution. The establishment of White Sands Missile Range in 1944 and White Sands Test Facility in 1963 has supported the city’s growth and employment because Las Cruces is the nearest city to each.

Acknowledgement

Las Cruces CVB

http://www.lascrucescvb.org/html/las_cruces__new_mexico_history.html

Las Vegas

Las Vegas can claim some interesting characters as part of its draw to tourists as a true town of the Old West. Doc Holliday had a dentist’s office in town. Billy the Kid hung out there. Teddy Roosevelt visited and recruited many of his Rough Riders from the local population for the Spanish-American War.

The twenty-nine Spanish settlers, who founded the city in 1835, received the Las Vegas land grant from the Mexican government, laying out their fledgling town in the traditional Spanish manner, with a large central plaza anchoring the surrounding community. Las Vegas was New Mexico's first territorial capital—for one day. As the first New Mexican settlement encountered by supply trains on their journey on the Santa Fe Trail traveling from the United States, jobs and commerce increased as the town grew to over 1,000 people by 1860. During the next 20 years, its population quadrupled as it established itself as a major trade center, with businesses as well as residences lining the plaza. The arrival of the railroad in 1879 solidified the city’s position as a mercantile center. At its peak, Las Vegas’ trade area included all of eastern New Mexico and western Texas. A long period of economic decline followed the 1930’s Depression.

The Montezuma Hotel, later known as Montezuma Castle, was built in 1882 as a hot springs resort by the Fred Harvey Company and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, becoming the first building in New Mexico with electric lights. The resort hotel, close to the Montezuma Hot Springs, was a popular destination for travelers making the crossing from east to west and back. The Castle closed in 1903 and deteriorated; in 1981 the Armand Hammer Foundation bought the property locating the American campus of the United World College there. Tours are still being given.

The city’s long dormancy was a boon to historic preservation, since it stopped development and permitted an architectural feast for the many people who visit Las Vegas today. There are over 900 structures in Las Vegas that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Northeast of Las Vegas is Fort Union National Monument. Established in 1851 to provide escort and protection for travelers on the west end of Santa Fe Trail, Fort Union grew to be the largest fort in the American Southwest, functioning as a military garrison, territorial arsenal, and military supply depot for the region.

Acknowledgements

Southwest Aviator

http://www.swaviator.com/html/issueMA04/lasvegasnm.html#Anchor-927

New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/16/travel/escapes/16american.html

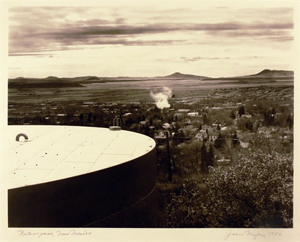

Raton

Raton Pass had been used by Spanish explorers and Indians for centuries to cut through the rugged Rocky Mountains, but the trail was too rough for wagons on the Santa Fe Trail. Raton was founded at the site of Willow Springs, a stop on the Santa Fe Trail. The original 320 acres for the Raton town site were purchased from the Maxwell Land Grant in 1880. In 1879, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad bought a local toll road and established a busy rail line. Raton quickly developed as a railroad, mining and ranching center for the northeast part of the New Mexico territory, as well as the county seat and principal trading center of the area. In the early 1900’s, a visitor could have stayed at Raton’s Gate City Motel for $1.25 a night.

Raton Pass had been used by Spanish explorers and Indians for centuries to cut through the rugged Rocky Mountains, but the trail was too rough for wagons on the Santa Fe Trail. Raton was founded at the site of Willow Springs, a stop on the Santa Fe Trail. The original 320 acres for the Raton town site were purchased from the Maxwell Land Grant in 1880. In 1879, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad bought a local toll road and established a busy rail line. Raton quickly developed as a railroad, mining and ranching center for the northeast part of the New Mexico territory, as well as the county seat and principal trading center of the area. In the early 1900’s, a visitor could have stayed at Raton’s Gate City Motel for $1.25 a night.

Dr. James Jackson Shuler served as mayor of Raton from 1899-1902 and 1910-1919, undertaking a number of impressive projects, including development of a Raton city park, electric and water filtration plant, Raton Water Works, Raton Public Library, and the construction of the municipal auditorium, the Shuler Theater, whose first production was a national touring company show of The Red Rose, a Victorian musical comedy that opened April 27, 1915.

Acknowledgement

City of Raton

http://www.ratonnm.gov/

Roswell

Blackdom was a small self-sufficient African-American community eighteen miles south of Roswell. Established in the early 1900s, it was an epicenter of social life during its heyday before succumbing to ghost town status in 1929. Blackdom was known far and wide for its famous mouth-watering pies and its Fourth of July and Juneteenth celebrations. At one point, it was even hailed for being the only community in the state with a college-educated teacher. October 26, 2002, was proclaimed Blackdom Day by the governor of New Mexico, and a historical marker was erected at a rest stop on Highway 285, between Roswell and Artesia to commemorate the community.

The 24,536-acre Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1937 to provide habitat for thousands of migrating sand hill cranes and waterfowl. It is one of more than 500 refuges throughout the United States managed by the Fish and Wildlife Service. The National Wildlife Refuge System is the only national system of lands dedicated to conserving our wildlife heritage for people today and for generations yet to come, providing habitat for some of the most rare creatures in New Mexico.

The Roswell Museum and Art Center opened in 1937, deriving its initial support from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as part of a Depression era project to promote public art centers nationwide. It was founded through an agreement with the City of Roswell, the WPA and Federal Art Project, the Chaves County Archaeological and Historical Society, and the Roswell Friends of Art. In its proposed plan, the WPA established that “the root of the community art center idea is participation by the entire community in all forms of art experience…” The stated purpose of the Museum was “to serve the art needs of Roswell [through] continuously changing exhibitions in the fine and practical arts, lectures and gallery talks [music programs and an art school where classes were offered free to the public]. The Museum has expanded, proving itself a popular stopping point for tourists visiting Chaves County.

Roswell's more recent history includes a mysterious crash of a supposed UFO that occurred north of the city in 1947. Responsible local citizens who witnessed the crash remained quiet about the doings until they retired. When their story surfaced, the city received world attention. Local business people encouraged the idea of a home for information on the Roswell Incident and other UFO phenomena; in 1992 the Roswell UFO Museum was opened to the public. The result has been thousands of people visiting annually and a new multi-million dollar tourism industry for the city.

Acknowledgements

New Mexico Tourism Department

http://www.newmexico.org/learn/wildlife/bitterlake.php

International UFO Museum and Research Center

http://www.roswellufomuseum.com

Roswell Museum and Art Center

http://roswellmuseum.org

Santa Fe

Santa Fe draws more than one million visitors annually.

The Native Americans that inhabited New Mexico long before Spanish contact continue to enrich the state today. There are nineteen pueblos located around the state; the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos surrounding Santa Fe offer an invitation to experience the timeless cultures, traditions, arts and beliefs of the Puebloans at Feast Days and Dances year-round.

Santa Fe is recognized as one of the most intriguing urban environments in the nation, due largely to the city's preservation of historic buildings and a modern zoning code, passed in 1958, that mandates the city's distinctive Spanish-Pueblo style of architecture based on the adobe (mud and straw) and wood construction of the past.

Santa Fe has also been the region's seat of culture and civilization (see the earlier section on “Tourism and the Arts” for an extensive discussion on its role as an art center). In fact, Santa Fe is considered one of the most distinctive arts destinations in the country; in 2005, Santa Fe became the first U.S. city to be chosen by UNESCO as a Creative City, one of only nine cities in the world to hold this designation.

Santa Fe's history as a capital city dates to 1610, when conquistador Don Pedro de Peralta established it as the capital for the Spanish "Kingdom of New Mexico." The Palace of the Governors, built in 1610, served as Spain's seat of government; it is the oldest public building in the country and now houses the state's history museum. Today's New Mexico State Capitol, known as the Roundhouse, is the only round capitol building in the country. It combines elements of New Mexico Territorial style, Pueblo adobe architecture and Greek Revival adaptations.

Other aspects of “The City Different,” that have attracted visitors both past and present:

- In the early 20th century many people were drawn to Santa Fe's dry climate as a cure for tuberculosis. These “lungers” were artists, politicians and scientists who came to the region seeking a healthier lifestyle. Spas and healing centers abound; the city’s many healing centers offer old and new modalities for attaining good health.

- In 1956 John Crosby built the Santa Fe Opera, which has developed into one of America's premier summer opera festivals, drawing 77,000 people to its open-air theater where the view is almost as exciting as the music.

- The city is surrounded by thousands of acres of pristine wilderness in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and is an ideal location for hikers, skiers, snowshoers, mountain bikers, river rafters, and horseback riders.

Acknowledgements

Santa Fe Convention and Tourist Bureau

http://santafe.org/

http://santafe.org/Visiting_Santa_Fe/About_Santa_Fe/index.html

Taos

The city of Taos is located close to the Taos Pueblo, the village and tribe from which it takes its name. Taos Pueblo’s multi-storied adobe buildings have been continuously inhabited for over 1000 years, and is the only living Native American community designated both a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and a National Historic Landmark. In a landmark decision in 1970, the U.S. government returned sacred Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo.

The city of Taos is located close to the Taos Pueblo, the village and tribe from which it takes its name. Taos Pueblo’s multi-storied adobe buildings have been continuously inhabited for over 1000 years, and is the only living Native American community designated both a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and a National Historic Landmark. In a landmark decision in 1970, the U.S. government returned sacred Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo.

As the town of Taos grew, it played an active role in the tumultuous history of New Mexico. In the 1700’s it became a base of operation and a refuge for the predominantly French-Canadian and American trappers and traders; the Taos Trade Fair became even more popular as a result of their presence. As the town settled and civilized, it also slowly began to draw tourists. In 1898 the first American artists, Ernest Blumenschien and Bert Phillips arrived when their wagon wheel broke. They were inspired to stay, and later to establish an Artist Colony. Like Santa Fe, Taos became a seat of culture in the early 20th century (see the earlier section on “Tourism and the Arts” for an extensive discussion on its role as an art center) continuing to attract artists and art lovers to the present day.

Other attractions that have made Taos a major tourist destination in the 21st century are:

- The historic homes of Kit Carson (frontiersman), Mabel Dodge Luhan (arts patron), D.H. Lawrence (writer), and Padre Antonio José Martínez (early Parish priest, rancher, and community leader), Taos Plaza, one of the few places in the country where the American flag may be properly displayed day and night,

- San Francisco de Asis Church in Ranchos de Taos, an adobe church painted and photographed by almost every noted artist who has visited the town for its sculptural beauty.

- In 1955, Ernie Blake created Taos Ski Valley, and to this day skiers are attracted to Taos.

Acknowledgments

Taos County Historical Society

http://www.taos-history.org/time.html

Taos Chamber of Commerce

www.taoschamber.com/

Taos Pueblo

http://www.taospueblo.com/about.php

Tourism Today

Tourism is big business for the people, cities, and state of New Mexico. The travel industry:

- is the largest private sector employer,

- is the second largest private sector industry in the state,

- employs more than 110,000 workers,

- generates payroll in excess of $1 Billion, and

- travelers spend more than $5.7 Billion in New Mexico annually.

In addition to the traditional forms of tourism that travelers look for, both the cities and state have developed innovative offerings to attract travelers of all interests, incomes, and ages:

- Creative Tourism,

- Agritourism,

- Cultural and Heritage Tourism,

- Sustainable Tourism,

- Culinary Tourism,

- Eco-tourism,

- Astronomy Tourism,

- Gaming Tourism,

- Film Tourism.

Acknowledgments

New Mexico Tourism Department

http://www.newmexico.org/

Tourism Association of New Mexico

http://www.tanm.org/