Background

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, “The Royal Road of the Interior Land,” was a rugged, often dangerous route running 1,600 miles from Mexico City to the royal Spanish town of Santa Fe from 1598 – 1882. During its first two centuries, El Camino Real brought settlers, goods and information to the province and carried its crops, livestock and crafts to the markets of greater Mexico. When Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, its northern frontier was opened to foreign trade, and New Mexico soon became the destination of a steady stream of traders carrying goods along the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri. El Camino Real connected with the Santa Fe Trail at Santa Fe and became the essential link between the growing U.S. economy and the long-established Mexican economy for the next 60 years.

This ancient road transcends time and place for its contribution to the history of two nations, with Indian, Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-American cultures each leaving their influence. Historic, ethnic, and cultural traditions were transmitted through El Camino Real. Aside from Western Civilization’s cultural values, a significant Hispanic culture survives today in the form of music, folktales, folk medicine, folk sayings, architecture, geographic place names, language, Catholic Religion, irrigation systems, and Spanish laws. Among the many food exchanges along the Camino Real was the red chile pepper, introduced into New Mexico by Spanish settlers from Mexico. The apple and other fruits were also introduced by settlers. Cattle, oxen, horses, mules, sheep, and goats – not to mention cats and dogs – were taken north to the New Mexican settlements.

Among the legal concepts presently utilized in the American legal system transmitted through El Camino Real are community property laws, land grant administration, first-priority in terms of water usage, mining claims, and the idea of sovereignty especially as applied to Native American land claims.

Description

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro consisted of several extensive sections along with a number of parajes, a Spanish term referring to a camping place where travelers customarily stopped for the night. A paraje can be a town, a village, a pueblo, or simply a good location for stopping. Paraje typically are spaced 10 to 15 miles apart and feature abundant water and fodder for the traveler’s animals. A jornada is an arduous trail between two parajes that must be traveled in one day’s time because of lack of a water supply. One notable paraje on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro is El Rancho de las Golondrinas in La Cienega located between the Rio Grande and Santa Fe. Fort Craig and Fort Selden were also located along the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro consisted of several extensive sections along with a number of parajes, a Spanish term referring to a camping place where travelers customarily stopped for the night. A paraje can be a town, a village, a pueblo, or simply a good location for stopping. Paraje typically are spaced 10 to 15 miles apart and feature abundant water and fodder for the traveler’s animals. A jornada is an arduous trail between two parajes that must be traveled in one day’s time because of lack of a water supply. One notable paraje on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro is El Rancho de las Golondrinas in La Cienega located between the Rio Grande and Santa Fe. Fort Craig and Fort Selden were also located along the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

The first leg of El Camino Real was the route of Hernando Cortez, conqueror of the Aztec empire in 1521, who landed at the Mexican port city of Veracruz, connecting Spain to the new world, and marched his troops to Mexico City.

When silver was discovered in the mountains of Zacatecas, the heavily traveled road from Mexico City to the silver mines at Zacatecas, what originally had been an Aztec foot trail, became the second leg of El Camino Real.

The Rio Grande Pueblo Indian Trail, an ancient trade route that supplied Southwestern Indians with important trade goods, became the third leg or upper part of the Camino Real. Juan de Onate received permission from the King of Spain to conduct the first colonization expedition into the interior of what is today New Mexico using the Mexico City to Zacatecas trail and on to the Rio Grande Pueblo Indian Trail.

At this time explorers funded their own expeditions. The crown did not supply money, troops, colonists, or equipment. The only thing the Spanish crown supplied was its permission to go forth and risk one’s life and fortune. On January 26, 1598 Onate’s expedition enlisted 170 families and 230 single men to join his expedition. In addition 500 soldiers joined the ranks. Onate also included the Catholic Church in his expedition by recruiting the Franciscan priest Fray Rodrigo Duran who brought several other Franciscan priests with him. Five thousand head of livestock rounded out the future colonists’ holdings.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro represented the longest trade route in North America and a significant trail for the settlement of the Southwest. Onate established the settlement at San Gabriel. A few years later, Don Pedro de Peralta moved the small colony of San Gabriel to the newly founded town of La Ciudad de Santa Fe de San Francisco (City of the Holy Faith of St. Francis), which then became the trail’s terminus.

The Jornada del Muerto was one of the most feared sections along El Camino Real. It was a dreaded 90-mile waterless shortcut bypassing the 120-mile long westward “bend” of the Rio Grande. Following the river in this region, it was also treacherous, with deep arroyos, canyons, and quick sand, slowing travel considerably. At 8-10 miles per day for a caravan, this shortcut saved several days on the trail. Many would cross the flat, dry desert passage in a forced march, traveling all day and all night to shorten the trip to three days. This short cut would often claim some of the draft animals for want of water, fulfilling its name “Journey of Death.” Occasional attacks from the Apaches was yet another hazard along the portion of the trail, making the Jornada del Muerto one of the most deadly stretches of El Camino Real.

The Jornada del Muerto was one of the most feared sections along El Camino Real. It was a dreaded 90-mile waterless shortcut bypassing the 120-mile long westward “bend” of the Rio Grande. Following the river in this region, it was also treacherous, with deep arroyos, canyons, and quick sand, slowing travel considerably. At 8-10 miles per day for a caravan, this shortcut saved several days on the trail. Many would cross the flat, dry desert passage in a forced march, traveling all day and all night to shorten the trip to three days. This short cut would often claim some of the draft animals for want of water, fulfilling its name “Journey of Death.” Occasional attacks from the Apaches was yet another hazard along the portion of the trail, making the Jornada del Muerto one of the most deadly stretches of El Camino Real.

There are numerous stories concerning how the Jornada del Muerto, got its name. Though often translated as “Journey of the Dead Man,” this is incorrect. The genesis of the name is well documented to the late 1600’s Governor of New Spain (New Mexico), Antonio de Otermin. In August 1680 the Pueblo Revolt forced retreat of the Spanish. Governor Otermin found 2,520 refugees congregated at Paraje Fra Cristobal. Most were suffering from exposure, starvation and sickness. Otermin had no choice except to order the continuation of the retreat to El Paso, 120 miles to the south, and the next inhabited settlement where they would find food and relief. On September 14, 1680, they entered the waterless desert passage for what turned into a grueling nine-day death march. Over 500 perished on the trail. Governor Otermin called it a “Journey of Death,” or in Spanish, Jornada del Muerto. The group arrived in El Paso with 1,946, a total loss of 574 souls.

In 1698, when the reoccupation of New Mexico began, the deadly march had become legend, and the name of the desert expanse, Jornada del Muerto, firmly christened. For over 300 years, this deadly portion of the trail lived up to its name.

In the later days of the trail, beginning in 1848, the U.S. Army built numerous forts to protect travelers along El Camino Real. Fort Craig was built in 1854, south of Socorro, to primarily protect travelers through the Jornada del Muerto. Fort Selden, north of Las Cruces, was added in 1864 near the San Diego river crossing and paraje. Both forts provided soldiers to escort caravans and travelers through the Jornada, and patrols looking for those in distress. Buffalo soldiers, the nickname given to the African American cavalry by the Native American tribes they fought, were often used for escort service through the Jornada del Muerto.

During colonial times, La Bajada Hill was the dividing line between the two great economic and governmental regions of Hispanic New Mexico: the Rio Abajo (lower river district) and the Rio Arriba (upper river district). The large sprawling mesa on whose edge La Bajada is located is called La Mojada, “sheepfold”, or “place where shepherds keep their flocks”, but because the road from Santa Fe to the Rio Abajo descended from the mesa here, the escarpment took the name La Bajada, “the descent.” At this point in their journey, travelers on El Camino Real could choose one of three ways to reach Santa Fe: (1) La Bajada Hill was the most difficult; (2) the Santa Fe River Canyon (La Boca) was the most often selected; and (3) traveling Galisteo Creek, over the escarpment in the Luna Lopez Grant.

During colonial times, La Bajada Hill was the dividing line between the two great economic and governmental regions of Hispanic New Mexico: the Rio Abajo (lower river district) and the Rio Arriba (upper river district). The large sprawling mesa on whose edge La Bajada is located is called La Mojada, “sheepfold”, or “place where shepherds keep their flocks”, but because the road from Santa Fe to the Rio Abajo descended from the mesa here, the escarpment took the name La Bajada, “the descent.” At this point in their journey, travelers on El Camino Real could choose one of three ways to reach Santa Fe: (1) La Bajada Hill was the most difficult; (2) the Santa Fe River Canyon (La Boca) was the most often selected; and (3) traveling Galisteo Creek, over the escarpment in the Luna Lopez Grant.

Later History

Historians give the date 1885 as the death of El Camino Real, when the railroad effectively made the trail obsolete. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad closely follows El Camino Real including through the Jornada del Muerto.

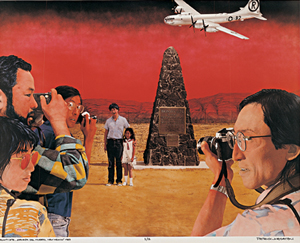

In 1945, the U.S. Army chose the desolate Jornada del Muerto to detonate the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site. The North American Trade Agreement became fully implemented on January 1, 2008. There are four corridors established in the agreement one of which is the Central Western corridor. It has the second largest trade volume of all the North American corridors. The route links Chihuahua in Mexico to Denver, Colorado, via the Paso del Norte, the ports of entry of El Paso/Ciudad Juarez between Chihuahua and Texas, and Santa Teresa in New Mexico.

In 1945, the U.S. Army chose the desolate Jornada del Muerto to detonate the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site. The North American Trade Agreement became fully implemented on January 1, 2008. There are four corridors established in the agreement one of which is the Central Western corridor. It has the second largest trade volume of all the North American corridors. The route links Chihuahua in Mexico to Denver, Colorado, via the Paso del Norte, the ports of entry of El Paso/Ciudad Juarez between Chihuahua and Texas, and Santa Teresa in New Mexico.

El Camino Real remains alive and well. Today Interstate I-25 serves the same purpose as the original trail, following the historic route along the west side of the Rio Grande quite closely. The 400 mile route within the United States was designated a National Historic Trail on October 3, 2000 and is currently overseen by both the National Park Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Today the Jornada del Muerto contains some of the best-preserved sections of El Camino Real.

The El Camino Real International Heritage Center is one of New Mexico's newest State Monuments, dedicated in November 2005. The Center contains award winning exhibits, an interpretive learning center, and artifacts presenting the history and heritage of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro—The Royal Road to the Interior.