Although entrepreneurs Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and John Woodruff of Springfield, Missouri deserve most of the credit for promoting the idea of an interregional link between Chicago and Los Angeles, their lobbying efforts were not realized until their dreams merged with the national program of highway and road development.

While legislation for public highways first appeared in 1916, with revisions in 1921, it was not until Congress enacted an even more comprehensive version of the act in 1925 that the government executed its plan for national highway construction. Officially, the numerical designation "66" was assigned to the Chicago-to-Los Angeles route in the summer of 1926. With that designation came acknowledgment as one of the nation's principal east-west arteries. From the outset, public road planners intended U.S. 66 to connect the main streets of rural and urban communities along its course for the most practical of reasons: most small towns had no prior access to a major national thoroughfare.

Route 66 was a highway spawned by the demands of a rapidly changing America. Its diagonal course linked hundreds of predominantly rural communities in Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas to Chicago; thus enabling farmers to transport grain and produce for redistribution. The diagonal configuration of Route 66 was particularly significant to the trucking industry, which by 1930 had come to rival the railroad for preeminence in the American shipping industry. The abbreviated route between Chicago and the Pacific coast traversed essentially flat prairie lands and enjoyed a more temperate climate than northern highways, which made it especially appealing to truckers.

In his famous social commentary, The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck proclaimed U.S. Highway 66 the "Mother Road." Steinbeck's classic 1939 novel, combined with the 1940 film recreation of the epic odyssey, served to immortalize Route 66 in the American consciousness. An estimated 210,000 people migrated to California to escape the despair of the Dust Bowl. In the minds of those who endured that particularly painful experience, and in the view of generations of children to whom they recounted their story, Route 66 symbolized the "road to opportunity." From 1933 to 1938 thousands of unemployed male youths from virtually every state were put to work as laborers on road gangs to pave the final stretches of the road. As a result of this monumental effort, the Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway was reported as "continuously paved" in 1938. Route 66 symbolized the renewed spirit of optimism that pervaded the country after economic catastrophe and global war. Often called, "The Main Street of America", it linked a remote and under-populated region with two vital 20th century cities – Chicago and Los Angeles.

In his famous social commentary, The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck proclaimed U.S. Highway 66 the "Mother Road." Steinbeck's classic 1939 novel, combined with the 1940 film recreation of the epic odyssey, served to immortalize Route 66 in the American consciousness. An estimated 210,000 people migrated to California to escape the despair of the Dust Bowl. In the minds of those who endured that particularly painful experience, and in the view of generations of children to whom they recounted their story, Route 66 symbolized the "road to opportunity." From 1933 to 1938 thousands of unemployed male youths from virtually every state were put to work as laborers on road gangs to pave the final stretches of the road. As a result of this monumental effort, the Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway was reported as "continuously paved" in 1938. Route 66 symbolized the renewed spirit of optimism that pervaded the country after economic catastrophe and global war. Often called, "The Main Street of America", it linked a remote and under-populated region with two vital 20th century cities – Chicago and Los Angeles.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which provided a comprehensive financial umbrella to underwrite the cost of the national interstate and defense highway system, began construction of a modern four-lane highway which by 1970 bypassed nearly all segments of the original Route 66. The outdated, poorly maintained vestiges of U.S. Highway 66 completely succumbed to the interstate system in October 1984 when the final section of the original road was bypassed by Interstate 40 at Williams, Arizona.

Route 66 and New Mexico: Past and Present

Route 66 was first laid out in 1926. Back then it followed the Old Pecos Trail from Santa Rosa through Dilia, Romeroville, and Pecos to Santa Fe. From Santa Fe it went over La Bajada Hill and down to Albuquerque.

Route 66 was first laid out in 1926. Back then it followed the Old Pecos Trail from Santa Rosa through Dilia, Romeroville, and Pecos to Santa Fe. From Santa Fe it went over La Bajada Hill and down to Albuquerque.

In 1937 the New Mexico section of the highway was shortened by 107 miles. This more-direct route bypassed Santa Fe. By the end of 1937, the paving of Route 66 throughout the entire State was complete, making Route 66 New Mexico’s first fully paved highway. This is the route that would be followed by the new Interstate years later.

Today there are over 260 miles of pre-interstate era Route 66 that remains drivable. In a few places, the old road is still designated as state highway, although none continue to carry the U.S. 66 designation. Other portions have reverted back to county or tribal maintenance. The remaining miles have long since been "covered over" with super highway I-40.

To further the preservation of the Mother Road and the many historic landmarks along the old sections of the highway, New Mexico established those original roads still open to traffic as a National Scenic Byway in 1994. Starting at the New Mexico/Texas State Line, the byway travels 300 miles through compelling, scenic, and dramatic stretches of the famed highway.

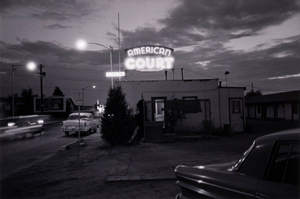

Another major undertaking in New Mexico was the Route 66 Neon Sign Restoration project by the New Mexico Route 66 Association. The Association led a tremendous effort along Route 66, restoring vintage neon signs in Tucumcari, Santa Rosa, Moriorty, Albuquerque, Grants, and Gallup. As a result, business owners, as well as entire communities, have a renewed pride in their Mother Road heritage.

Another major undertaking in New Mexico was the Route 66 Neon Sign Restoration project by the New Mexico Route 66 Association. The Association led a tremendous effort along Route 66, restoring vintage neon signs in Tucumcari, Santa Rosa, Moriorty, Albuquerque, Grants, and Gallup. As a result, business owners, as well as entire communities, have a renewed pride in their Mother Road heritage.