Culture Rush

The history of art in New Mexico begins with the earliest inhabitants, the Paleo-Indians, who developed their arts over thousands of years, and left artifacts buried in ruins and mysterious images drawn on canyon walls. Eventually Native Americans, first the Pueblo culture, followed by the Apache and Navajo, settled permanently in New Mexico. These early artists created designs and images based on strong spiritual connections to the surrounding natural world.

The history of art in New Mexico begins with the earliest inhabitants, the Paleo-Indians, who developed their arts over thousands of years, and left artifacts buried in ruins and mysterious images drawn on canyon walls. Eventually Native Americans, first the Pueblo culture, followed by the Apache and Navajo, settled permanently in New Mexico. These early artists created designs and images based on strong spiritual connections to the surrounding natural world.

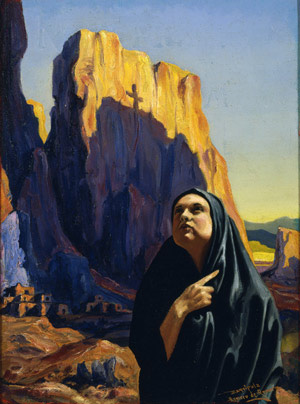

In the 1500s, the Spanish culture arrived and brought new ideas, including Christian iconography, and materials to the region such as metal, wool, paints and dyes. In the 1800s, the first European-American tourists began to visit via trail and train. The artists who followed were inspired by the region’s cultures and landscape, and they in turn brought new ideas and trends from their art world to the region. The artwork that has been produced in New Mexico since this time has been influenced by these the indigenous, Spanish and Anglo traditions and by the unique qualities of the region’s communities and natural environment.

In the 1500s, the Spanish culture arrived and brought new ideas, including Christian iconography, and materials to the region such as metal, wool, paints and dyes. In the 1800s, the first European-American tourists began to visit via trail and train. The artists who followed were inspired by the region’s cultures and landscape, and they in turn brought new ideas and trends from their art world to the region. The artwork that has been produced in New Mexico since this time has been influenced by these the indigenous, Spanish and Anglo traditions and by the unique qualities of the region’s communities and natural environment.

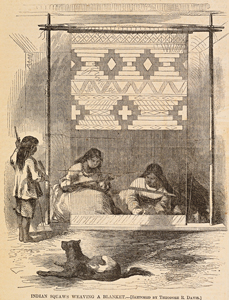

When the transcontinental train reached the territory of New Mexico in 1879, a “culture rush” began, and European-American artists and anthropologists hurried to the region to collect artworks and document native lifestyles before everything was changed by the influx of outsiders. The drawings, photographs and paintings that artists made at this time were often used to advertise the exotic Southwestern landscape, and the native people who lived here.

When the transcontinental train reached the territory of New Mexico in 1879, a “culture rush” began, and European-American artists and anthropologists hurried to the region to collect artworks and document native lifestyles before everything was changed by the influx of outsiders. The drawings, photographs and paintings that artists made at this time were often used to advertise the exotic Southwestern landscape, and the native people who lived here.

The first images of Native American cultures in New Mexico were made by artists, writers and photographers who were paid by journals such as Harper’s Weekly and Scribners. Illustrated articles about the Zuni tribe by Frank Hamilton Cushing and the Hispanic Penitente Brothers by Charles Fletcher Lummis are examples of popular articles from this time. Lummis went on to write many more articles about the peoples of the Southwest, and he helped create a mystique about the picturesque Southwestern cultures and land.

The first images of Native American cultures in New Mexico were made by artists, writers and photographers who were paid by journals such as Harper’s Weekly and Scribners. Illustrated articles about the Zuni tribe by Frank Hamilton Cushing and the Hispanic Penitente Brothers by Charles Fletcher Lummis are examples of popular articles from this time. Lummis went on to write many more articles about the peoples of the Southwest, and he helped create a mystique about the picturesque Southwestern cultures and land.

Photographers capitalized on this mystique and made postcards and calendars of Native Americans that created stereotypical images of the people who lived here. In 1902, the Fred Harvey Company built the Alvarado Hotel at the railroad station in Albuquerque. Part of the hotel was designated “The Indian Building” as a place where Native American artists sold their wares to tourists. This enterprise was successful, and the artists began to change their styles depending on what sold. Consequently the artwork became less authentic and more commercial. In time, prominent artists and anthropologists would try to fight the commercialization of indigenous arts, and influence the quality of work that was created.

Photographers capitalized on this mystique and made postcards and calendars of Native Americans that created stereotypical images of the people who lived here. In 1902, the Fred Harvey Company built the Alvarado Hotel at the railroad station in Albuquerque. Part of the hotel was designated “The Indian Building” as a place where Native American artists sold their wares to tourists. This enterprise was successful, and the artists began to change their styles depending on what sold. Consequently the artwork became less authentic and more commercial. In time, prominent artists and anthropologists would try to fight the commercialization of indigenous arts, and influence the quality of work that was created.

Statehood and a New Museum

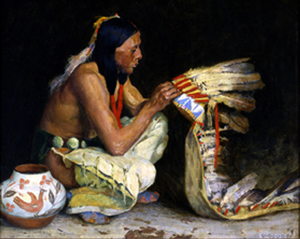

Edgar L. Hewett created thefirst art museum in New Mexico in 1917. Hewett was an anthropologist, teacher and administrator who played a pivotal role in turning Santa Fe into a center for art and anthropological research. After New Mexico became a state in 1912, Hewett created an economic plan based on developing cultural institutions and promoting the unique, indigenous qualities of Southwestern arts. After holding art exhibitions in the hi storic Palace of the Governors, Hewett’s Pueblo Spanish revival style art museum opened in 1917. As director, Hewett was committed to exhibiting work that mixed anthropology with art, such as Henry Balink’s painting Pueblo Pottery. Hewett was also committed to an “open door approach”, a policy promoted by the artist Robert Henri, which allowed any artist working in New Mexico to exhibit at the museum. This was a radical approach created in opposition to the exclusive academies that recognized only European academic art.

storic Palace of the Governors, Hewett’s Pueblo Spanish revival style art museum opened in 1917. As director, Hewett was committed to exhibiting work that mixed anthropology with art, such as Henry Balink’s painting Pueblo Pottery. Hewett was also committed to an “open door approach”, a policy promoted by the artist Robert Henri, which allowed any artist working in New Mexico to exhibit at the museum. This was a radical approach created in opposition to the exclusive academies that recognized only European academic art.

Hewett was also the director of the School for American Research, and as an anthropologist he was very involved with Native American artists . He created the “Santa Fe Program” initially to encourage potters from San Idelfonso to improve their wares. He lucked out by meeting Maria Martinez and her husband Julian, who became masters of their medium and invented the elegant, matte black and polished black pottery that became world renown. Hewett and his partner Kenneth Chapman worked with other Pueblo potters and encouraged the revival of ancient designs that were found on excavated pottery and petroglyphs throughout the Southwest.

Hewett was also the director of the School for American Research, and as an anthropologist he was very involved with Native American artists . He created the “Santa Fe Program” initially to encourage potters from San Idelfonso to improve their wares. He lucked out by meeting Maria Martinez and her husband Julian, who became masters of their medium and invented the elegant, matte black and polished black pottery that became world renown. Hewett and his partner Kenneth Chapman worked with other Pueblo potters and encouraged the revival of ancient designs that were found on excavated pottery and petroglyphs throughout the Southwest.

San Idelfonso day school teachers were influenced by the Santa Fe program and began a controversial project encouraging Native American students to draw pictures form their own experiences. At this time the Dawes Act supported the assimilation of native students into the mainstream society, and did not permit federal Indian School students to acknowledge their own traditions and lifestyles, or to speak their native languages. Students like Alfred Montoya continued the practice regardless, and pueblo easel painting was incorporated into the Santa Fe Program. In later years, Hewett would exhibit Pueblo easel paintings at the museum, and the artwork was highly appreciated by the local art community.

Modernism in New Mexico

In the beginning of the 20th century, there was a growing interest in the Southwest among European and American artists, and many came to visit, tour and work in New Mexico. Santa Fe and Taos became the most popular artist communities and the centers of the art scene. After statehood in 1912, a wave of academically-trained realist painters came who were attracted to the land, the light and the native cultures. They painted images of the native peoples, their homes and the surrounding landscape.

The 1913 Armory Show, in Chicago and New York, introduced the public to the most radical European and American art, and artists began to align themselves either with the new, the "modernists," or the old, "the academic realists." Modernist art expressed a more personal and emotional response to the world, rather than a replication, or mirror, of reality. In New Mexico, modernists were drawn to Santa Fe, where the Open Door policy of the Museum of Fine Arts created a place for progressive and modern artists to show their work. Well-known artists Robert Henri and his friend John Sloan were frequent visitors from the East Coast who drew other artists to Santa Fe. European-trained academic painters and illustrators mostly congregated in Taos. After WWI these communities broke into distinct societies that sometimes overlapped and sometimes opposed each other. As time went by, art from both groups became more modern and abstract.

The 1913 Armory Show, in Chicago and New York, introduced the public to the most radical European and American art, and artists began to align themselves either with the new, the "modernists," or the old, "the academic realists." Modernist art expressed a more personal and emotional response to the world, rather than a replication, or mirror, of reality. In New Mexico, modernists were drawn to Santa Fe, where the Open Door policy of the Museum of Fine Arts created a place for progressive and modern artists to show their work. Well-known artists Robert Henri and his friend John Sloan were frequent visitors from the East Coast who drew other artists to Santa Fe. European-trained academic painters and illustrators mostly congregated in Taos. After WWI these communities broke into distinct societies that sometimes overlapped and sometimes opposed each other. As time went by, art from both groups became more modern and abstract.

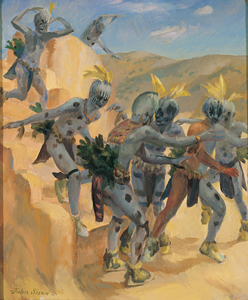

Academic painters based in Taos created pictures of Hispanic and Native American people engaged in everyday activities and religious rituals. These romantic and impressionistic pictures became some of the best-known art from New Mexico. Their images were both ethnographic studies and nostalgic portrayals of an almost bygone era. The Taos painters were exclusive about their membership, and at one point, had members deported if they were not U.S. citizens. Irving Couse, Joseph Henry Sharp and Victor Higgins were influential members of this group.

Academic painters based in Taos created pictures of Hispanic and Native American people engaged in everyday activities and religious rituals. These romantic and impressionistic pictures became some of the best-known art from New Mexico. Their images were both ethnographic studies and nostalgic portrayals of an almost bygone era. The Taos painters were exclusive about their membership, and at one point, had members deported if they were not U.S. citizens. Irving Couse, Joseph Henry Sharp and Victor Higgins were influential members of this group.

In Santa Fe, five young artists formed Los Cinco Pintores on the idea of bringing art directly to the people . Will Shuster and Jozef Bakos were influential members of this group. The Santa Fe artists were somewhat notorious for wild parties and drinking in the time of prohibition. The social conservatism of the political leadership in Santa Fe did not approve of their life style, or their progressive political views.

In Santa Fe, five young artists formed Los Cinco Pintores on the idea of bringing art directly to the people . Will Shuster and Jozef Bakos were influential members of this group. The Santa Fe artists were somewhat notorious for wild parties and drinking in the time of prohibition. The social conservatism of the political leadership in Santa Fe did not approve of their life style, or their progressive political views.

Another group known as the"New Mexico artists" attracted more modernist painters. The coalition did not last long, but members such as Andrew Dasburg, Gustave Baumann, and Randall Davey have had a long and lasting impact on the arts in New Mexico.

.jpg) Artists in these different groups also worked together. In 1925, Will Shuster and Gustave Baumann built a human-sized marionette in their backyard and named him “Zozobra”, or Old man Gloom, and burned it during the Santa Fe Fiesta. Their objective was to burn away gloom, and to express their disapproval of the commercialized tourism that was taking over the authentic Santa Fe that they loved. The burning of Zozobra became a tradition and the most notorious event of the annual Santa Fe Fiesta.

Artists in these different groups also worked together. In 1925, Will Shuster and Gustave Baumann built a human-sized marionette in their backyard and named him “Zozobra”, or Old man Gloom, and burned it during the Santa Fe Fiesta. Their objective was to burn away gloom, and to express their disapproval of the commercialized tourism that was taking over the authentic Santa Fe that they loved. The burning of Zozobra became a tradition and the most notorious event of the annual Santa Fe Fiesta.

Modernism’s Second Wave

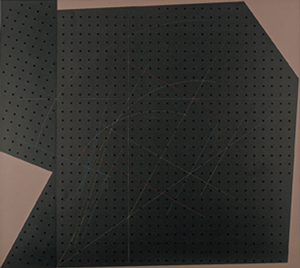

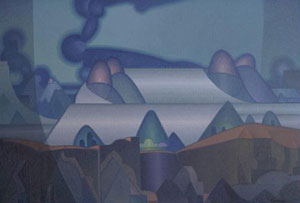

Hewett was more interested in ethnic imagery than abstraction and modernism. However, he did stay true to his policy of allowing any style of art to hang at the museum by scheduling regular exhibitions of local artists working with abstraction. Raymond Jonson was in charge of these exhibits, and he took the opportunity to present work contrary to the predictable Southwestern ethnographic genre. Jonson and his fellow abstractionist Emil Bisttram spearheaded a group of painters known as the Transcendental Painting group. Their mission was to create non-objective work that did not refer to the natural world.

Hewett was more interested in ethnic imagery than abstraction and modernism. However, he did stay true to his policy of allowing any style of art to hang at the museum by scheduling regular exhibitions of local artists working with abstraction. Raymond Jonson was in charge of these exhibits, and he took the opportunity to present work contrary to the predictable Southwestern ethnographic genre. Jonson and his fellow abstractionist Emil Bisttram spearheaded a group of painters known as the Transcendental Painting group. Their mission was to create non-objective work that did not refer to the natural world.

In Taos, a new group of itinerant modernist artists formed around the writer Mabel Dodge. Dodge had come from New York in 1917, originally with her painter husband whom she quickly divorced after she arrived. She married Tony Luhan from Taos Pueblo shortly thereafter . Mabel had been the center of a radical salon of artists, writers, intellectuals, socialists and activists in New York, and she invited her friends to visit her in New Mexico.

One of the first artists to visit Dodge was Marsden Hartley, who was searching for a uniquely American approach to painting. Later she would be visited by Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Paul Strand and Rebecca Salsbury James, all prominent painters and photographers who were creatively inspired by their New Mexico visits and experiences. This group of artists were mostly associated through the gallery that Alfred Stieglitz, O’Keeffe’s husband, ran in New York City.

One of the first artists to visit Dodge was Marsden Hartley, who was searching for a uniquely American approach to painting. Later she would be visited by Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Paul Strand and Rebecca Salsbury James, all prominent painters and photographers who were creatively inspired by their New Mexico visits and experiences. This group of artists were mostly associated through the gallery that Alfred Stieglitz, O’Keeffe’s husband, ran in New York City.

The Depression and the WPA

In 1929 the stock market crashed and the United States entered the great Depression. The tourism market in New Mexico crashed as well, and a period of prosperity for artists ended. Educational and vocational programs were developed to promote artistic and economic development in the state.

The Spanish Colonial Arts Society and the Colonial Hispanic Crafts School, in Galisteo were both formed in 1929 with the goal of encouraging and promoting traditional Hispanic arts. Traditional arts such as weaving, furniture making, tinwork, colcha embroidery and wood carving were taught and promoted. Taos and the smaller villages of Northern New Mexico were the centers for these activities, and both traditional and modern artists, philanthropists, intellectuals, and writers were involved in promoting interest in Hispanic arts. Romero de Romero became the best known Hispanic painter from New Mexico during this time.

The Spanish Colonial Arts Society and the Colonial Hispanic Crafts School, in Galisteo were both formed in 1929 with the goal of encouraging and promoting traditional Hispanic arts. Traditional arts such as weaving, furniture making, tinwork, colcha embroidery and wood carving were taught and promoted. Taos and the smaller villages of Northern New Mexico were the centers for these activities, and both traditional and modern artists, philanthropists, intellectuals, and writers were involved in promoting interest in Hispanic arts. Romero de Romero became the best known Hispanic painter from New Mexico during this time.

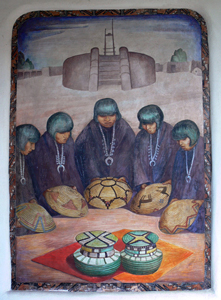

In 1932, Dorothy Dunn created the The Studio Program at the Santa Fe Indian School. Dunn was an art educator who felt that art instruction helped her Native American students master English and achieve academic success. She taught her students a painting style based on ledger drawings, Kiva murals and first generation Pueblo easel painters. She encouraged students to depict their cultural traditions and lifeways by using flat outlined forms, without 3-D perspective or modeling. Though the aesthetics were narrowly defined, Dunn’s students included the likes of Allan Houser and Pablita Velarde. The Studio program was a success and the new style of painting became a powerful force in New Mexican art. Dunn was succeeded by one of her students Geronima Cruz, and the program was continued until it was replaced by the Institute of American Indian Arts in 1962.

In 1932, Dorothy Dunn created the The Studio Program at the Santa Fe Indian School. Dunn was an art educator who felt that art instruction helped her Native American students master English and achieve academic success. She taught her students a painting style based on ledger drawings, Kiva murals and first generation Pueblo easel painters. She encouraged students to depict their cultural traditions and lifeways by using flat outlined forms, without 3-D perspective or modeling. Though the aesthetics were narrowly defined, Dunn’s students included the likes of Allan Houser and Pablita Velarde. The Studio program was a success and the new style of painting became a powerful force in New Mexican art. Dunn was succeeded by one of her students Geronima Cruz, and the program was continued until it was replaced by the Institute of American Indian Arts in 1962.

Federal Arts Projects

The PWAP (Public Works Arts Project) and the WPA (Works Progress Administration) were created during this time to support unemployed artists throughout the country. In New Mexico,160 artists created public art in 29 New Mexican communities . Will Shuster created 4 large murals to honor Pueblo Indians at the Museum of Fine Arts, through the short-lived PWAP. The WPA supported a wider range of projects in public buildings and supported artists and craftsmen making prints, paintings and photographs, as well as traditional Hispanic and Native American artworks.

The PWAP (Public Works Arts Project) and the WPA (Works Progress Administration) were created during this time to support unemployed artists throughout the country. In New Mexico,160 artists created public art in 29 New Mexican communities . Will Shuster created 4 large murals to honor Pueblo Indians at the Museum of Fine Arts, through the short-lived PWAP. The WPA supported a wider range of projects in public buildings and supported artists and craftsmen making prints, paintings and photographs, as well as traditional Hispanic and Native American artworks.

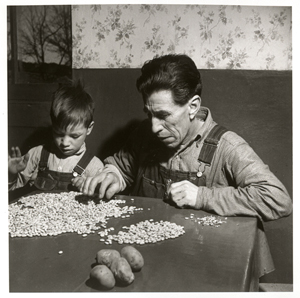

FSA, or Farms Security Administration photo project

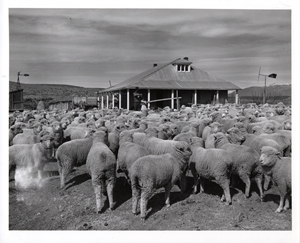

The FSA, or Farm Security Administration, hired photographers to document rural American lives during the Depression. John Collier Jr. and Russell Lee photographed in farming and ranching communities, small villages and along the highways crossing the state. Their documentary work has inspired many photographers who focus on the vernacular- on the everyday life of distinct American cultures and communities.

The FSA, or Farm Security Administration, hired photographers to document rural American lives during the Depression. John Collier Jr. and Russell Lee photographed in farming and ranching communities, small villages and along the highways crossing the state. Their documentary work has inspired many photographers who focus on the vernacular- on the everyday life of distinct American cultures and communities.

The Post-War Period

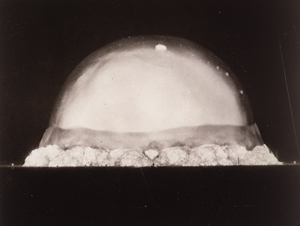

The romantic images of southwestern life seemed irrelevant after WWll. Los Alamos, NM was the home of the Manhattan project during the war years, and the Trinity Site near Alamogordo, NM was the site of the first atomic bomb explosion. Many New Mexicans had fought and died in the war, and the state became more connected to the rest of the country and world.

The romantic images of southwestern life seemed irrelevant after WWll. Los Alamos, NM was the home of the Manhattan project during the war years, and the Trinity Site near Alamogordo, NM was the site of the first atomic bomb explosion. Many New Mexicans had fought and died in the war, and the state became more connected to the rest of the country and world.

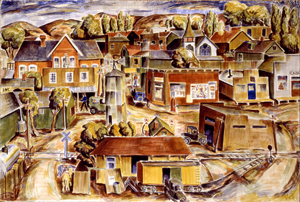

The arrival of the Atomic age ended New Mexico’s cultural and technological isolation. The postwar boom increased industry, transportation, tourism, and the population. Albuquerque became the population center, and the arts community at the end of the 1940s blossomed there as well. The University of New Mexico became the center of a thriving community of modernist artists.

The arrival of the Atomic age ended New Mexico’s cultural and technological isolation. The postwar boom increased industry, transportation, tourism, and the population. Albuquerque became the population center, and the arts community at the end of the 1940s blossomed there as well. The University of New Mexico became the center of a thriving community of modernist artists.

Raymond Jonson moved to Albuquerque to teach at the University and opened the Jonson gallery, the only gallery in New Mexico devoted to abstract and non-objective art. Jonson attracted a broad range of students to the university's Fine Arts  program, including returning veteran Richard Diebenkorn, from the San Francisco Bay area, and native son Joe H. Herrera. Though artists continued to congregate in the enclaves of Taos and Santa Fe, Albuquerque became the center for younger, more progressive artists.

program, including returning veteran Richard Diebenkorn, from the San Francisco Bay area, and native son Joe H. Herrera. Though artists continued to congregate in the enclaves of Taos and Santa Fe, Albuquerque became the center for younger, more progressive artists.

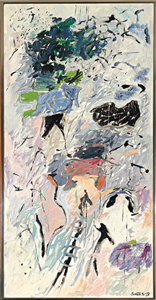

In the Cold War era of Sputnik and the arms race, science and technology became dominant forces in the culture. New Mexico became well-known for its scientific laboratories in Los Alamos and Sandia and the top scientists who migrated to the state. Artists working with abstraction embraced two opposing formalist strategies in response to the times and trends: rational/geometric styles and expressive/ intuitive styles.

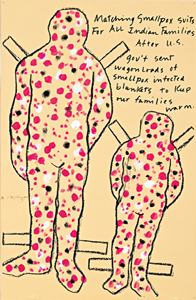

Native American art also began to change radically during the Cold War era. In 1962, the Institute of American Indian Arts replaced the Studio at the Indian School. The school hired new faculty who were engaged in contemporary issues and styles. Fritz Scholder became an important teacher there, and he energized a rebellion against the prevailing formalist styles of the day. Scholder combined Native American stereotypes with abstract expressionist brushstrokes. He influenced many young Native American artists including T. C. Cannon, who attacked Native American stereotypes and transformed them into political commentary. Subsequent movements in Native American arts became more political. Bob Haozous’ Apache Skull, and Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s Matching Smallpox Suits... have clear political messages about tragic events in Native American history.

Comtemporary Art and Pluralism

American art since the 1960s has been defined by many different movements and styles. In New Mexico, the 1960's Counter Culture, which attracted rebellious youth, political activists and back-to-the-earth hippies, encouraged the rejection of mainstream values and authority. Artists in the region moved away form modernism and began to develop multiple forms of artistic expression. Pop art, minimalist art, Conceptual art, Land art, political art, and feminist art, were movements that influenced New Mexican art during the post-modern age. Photographers continued to migrate to the state, to document the land and culture and to experiment with new processes and ways of picturing the world.

American art since the 1960s has been defined by many different movements and styles. In New Mexico, the 1960's Counter Culture, which attracted rebellious youth, political activists and back-to-the-earth hippies, encouraged the rejection of mainstream values and authority. Artists in the region moved away form modernism and began to develop multiple forms of artistic expression. Pop art, minimalist art, Conceptual art, Land art, political art, and feminist art, were movements that influenced New Mexican art during the post-modern age. Photographers continued to migrate to the state, to document the land and culture and to experiment with new processes and ways of picturing the world.

New Mexican artists investigated the atomic legacy in New Mexico’s history, and made artwork that challenged and informed our understanding of historic events. Multiculturalism is a defining characteristic of New Mexican art and Native American and Hispanic artists continue to assert their own culture and question the dominant Anglo culture through provocative artworks.

Today, New Mexico is still attracts artists, and Santa Fe is among the largest art makets in the nation. Museums, art centers, galleries, art markets and events also attract many tourists who come see the diversity of art and culture thriving in the state. New Mexico continues to be a place where the arts are highly valued, and where artists play a vital role in the state’s economy and culture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ancestral Pueblo Architecture

The Ancestral Pueblo people of the Four Corners area created the first permanent shelters in New Mexico. Their history is divided into two distinct periods, the Basketmaker and the Pueblo. The earliest Basketmaker shelters were built with rock and made use of canyon overhangs and caves. Shelters evolved into pithouses, underground dwellings with earth and timber roofs. Sometime after the year A.D. 700, rooms were built above ground; this is considered to be the Pueblo I period. The above ground shelters were made of stone and mud, and pithouses were still present in groups of buildings.In the Pueblo II period shelters included multi-storied houses constructed from stone masonry and subterranean ceremonial kivas. By the period known as Pueblo III, the Ancestral Pueblo people had evolved into extraordinary architects, masons and community planners.

The Ancestral Pueblo people of the Four Corners area created the first permanent shelters in New Mexico. Their history is divided into two distinct periods, the Basketmaker and the Pueblo. The earliest Basketmaker shelters were built with rock and made use of canyon overhangs and caves. Shelters evolved into pithouses, underground dwellings with earth and timber roofs. Sometime after the year A.D. 700, rooms were built above ground; this is considered to be the Pueblo I period. The above ground shelters were made of stone and mud, and pithouses were still present in groups of buildings.In the Pueblo II period shelters included multi-storied houses constructed from stone masonry and subterranean ceremonial kivas. By the period known as Pueblo III, the Ancestral Pueblo people had evolved into extraordinary architects, masons and community planners.

Chaco Canyon is a famous Pueblo III site in the four corners area and Pueblo Bonito, a “great house” in Chaco, is a fine architectural example of this period. Important characteristics of Pueblo Bonito include a D-shape plan with rectilinear buildings facing south for warmth, a large central plaza, and approximately 35 small kivas and 2 great kivas. The Chacoans were expert masons, and they used local sandstone, which they shaped into bricks and laid carefully in horizontal strata. The ruins that exist today are a testament to how well they were built.

Chaco Canyon is a famous Pueblo III site in the four corners area and Pueblo Bonito, a “great house” in Chaco, is a fine architectural example of this period. Important characteristics of Pueblo Bonito include a D-shape plan with rectilinear buildings facing south for warmth, a large central plaza, and approximately 35 small kivas and 2 great kivas. The Chacoans were expert masons, and they used local sandstone, which they shaped into bricks and laid carefully in horizontal strata. The ruins that exist today are a testament to how well they were built.

Archeologists believe that Chaco Canyon was an important spiritual center for the Ancestral Pueblo people, based on the great number of kivas, and the many spiritual objects found in the ruins. There is also a belief that Chaco buildings were carefully aligned in order to observe lunar and solar cycles. Periods of drought, and possibly other strife, caused the inhabitants of Chaco Canyon to leave by the 14th century.

After they left their settlements in the 1300s, the Pueblo people made their way to the Rio Grande and its tributaries, and to more mountainous settlements in western New Mexico. Pueblo IV architecture was made from “puddled adobe” (mud laid in horizontal layers to build up walls), stone and sod blocks. Multi-storied residences were geometrically arranged around large plazas that included ceremonial kivas. Doors and windows were minimized, and ladders were used to access upper level buildings. They were situated to make use of water and to provide protection from marauders.

Taos Pueblo was first settled during this period and it has been continuously occupied ever since. Over the centuries the pueblo grew into a beautiful arrangement of stacked and clustered blocks of buildings that have inspired architects, as well as painters and photographers, throughout recorded history.

Taos Pueblo was first settled during this period and it has been continuously occupied ever since. Over the centuries the pueblo grew into a beautiful arrangement of stacked and clustered blocks of buildings that have inspired architects, as well as painters and photographers, throughout recorded history.

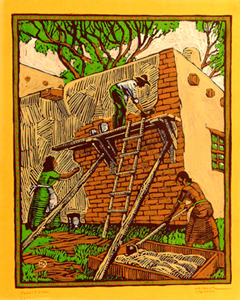

Adobe building changed after Spanish contact, beginning in 1593. Pueblo Indians adopted the Spanish technique of forming mud into sun dried adobe bricks. In the Pueblo V period, which began in the 1700s after the Spanish reconquest and continues to the present day , Spanish and Pueblo cultures shared and adapted construction techniques and design.

Zuni Pueblo is considered a Pueblo V building. The original, small community built of stone grew organically into a large multi-storied pueblo built with adobe bricks. Fireplaces, chimneys, horno ovens, parapets, and terraces were some of the architectural developments that occurred during the early Pueblo V period.

Zuni Pueblo is considered a Pueblo V building. The original, small community built of stone grew organically into a large multi-storied pueblo built with adobe bricks. Fireplaces, chimneys, horno ovens, parapets, and terraces were some of the architectural developments that occurred during the early Pueblo V period.

Spanish Colonial Architecture

While New Mexico was under Spanish rule, architectural developments occurred slowly. Spanish settlers were cut off from trade with their fellow North Americans. Supplies, as well as technology and ideas, had to come from far-away Spain. During these years of isolation, settlers lived a subsistence lifestyle and had little money or energy for developing architectural styles or engineering. Adobe homes were simple and made from basic local materials. Details included flat roofs, earthen floors sealed with animal blood, mud plaster, wooden bars on windows, vigas and latillas for the ceiling. Glass, nails, and hardware were not available. Communities were often arranged around a plaza for defensive purposes.

While New Mexico was under Spanish rule, architectural developments occurred slowly. Spanish settlers were cut off from trade with their fellow North Americans. Supplies, as well as technology and ideas, had to come from far-away Spain. During these years of isolation, settlers lived a subsistence lifestyle and had little money or energy for developing architectural styles or engineering. Adobe homes were simple and made from basic local materials. Details included flat roofs, earthen floors sealed with animal blood, mud plaster, wooden bars on windows, vigas and latillas for the ceiling. Glass, nails, and hardware were not available. Communities were often arranged around a plaza for defensive purposes.

Spain focused most of its effort and money on missionary activities. The mission churches were the most significant architecture during this period, and they have been painted and photographed by numerous artists over the years. Churches were built within Spanish communities in the northern mountains like at Rancho de Taos, Trampas and Chimayo, and in all of the Pueblos. The friars were in charge of Pueblo church design and engineering, and the Pueblo people supplied the hard labor. Though the history of the Pueblo mission churches is fraught with controversy and tragedy, the buildings themselves are known for their simple beauty, and they have provided inspiration for important developments in New Mexico architecture.

Territorial Architecture

With Mexican independence in 1821, New Mexico’s period of isolation ended. Trade on the Santa Fe Trail brought new people, cultures and materials. Glass, nails, hardware and tools were finally available.

With Mexican independence in 1821, New Mexico’s period of isolation ended. Trade on the Santa Fe Trail brought new people, cultures and materials. Glass, nails, hardware and tools were finally available.

In 1848, New Mexico became an official territory of the United States. American visitors who arrived in Santa Fe via the Santa Fe Trail did not always appreciate the native architecture. Some even said Santa Fe looked like a prairie dog town! Americans brought in milled posts and trim to make the buildings look more European, and built Greek Revival style buildings with white columns and classical proportions. U.S. military forts and government buildings adopted this style, now known as “Territorial.” Churches were also influenced by European design, and Bishop Lamy, who came from France, built Santa Fe’s St. Francis cathedral in the Romanesque Revival style.

In 1848, New Mexico became an official territory of the United States. American visitors who arrived in Santa Fe via the Santa Fe Trail did not always appreciate the native architecture. Some even said Santa Fe looked like a prairie dog town! Americans brought in milled posts and trim to make the buildings look more European, and built Greek Revival style buildings with white columns and classical proportions. U.S. military forts and government buildings adopted this style, now known as “Territorial.” Churches were also influenced by European design, and Bishop Lamy, who came from France, built Santa Fe’s St. Francis cathedral in the Romanesque Revival style.

In 1880, the railroad began to influence the architectural styles in new settlements. Towns built along the railroad like Deming, Albuquerque and Las Vegas resembled small Midwestern towns with Victorian houses, pitched metal roofing, and front porches. Towns not along the railroad, such as Santa Fe and Taos, retained more of their regional character.

In 1880, the railroad began to influence the architectural styles in new settlements. Towns built along the railroad like Deming, Albuquerque and Las Vegas resembled small Midwestern towns with Victorian houses, pitched metal roofing, and front porches. Towns not along the railroad, such as Santa Fe and Taos, retained more of their regional character.

Pueblo Spanish Revival Architecture

After statehood, in 1912, New Mexico began to grow and change more quickly. Politicians, businessmen, artists and archeologists were involved in making decisions about how New Mexico should grow. Tourism was the key to economic development, and the “Santa Fe Plan” was created to promote and maintain a characteristic regional style based on ancient pueblo architecture. The model for this architecture was the mission churches of Acoma and Isleta, and the sculpted adobe masses of Taos Pueblo. The New Mexico Museum of Art and the La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, both built by the architectural firm of Rapp and Rapp, first set the example for this type of building. Spanish colonial details such as carved and painted vigas, herringbone patterned latillas, and hand-carved furniture were also incorporated in these buildings. This became known as “Pueblo Spanish Revival” or “Santa Fe Style.”

The Fred Harvey Company built hotels and train stations with the objective of luring tourists to ride the railroad. The railroad financed the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque and the La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe. The building designs were based on the Pueblo Spanish style, and Mary Colter, the interior designer, incorporated Native American designs, symbols, weavings and traditional artworks into the private rooms and public spaces.

The Fred Harvey Company built hotels and train stations with the objective of luring tourists to ride the railroad. The railroad financed the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque and the La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe. The building designs were based on the Pueblo Spanish style, and Mary Colter, the interior designer, incorporated Native American designs, symbols, weavings and traditional artworks into the private rooms and public spaces.

The first New Mexican architect to invest in and develop the Pueblo Spanish Revival style was John Gaw Meem. Meem was trained as an engineer and came to Santa Fe to receive treatment for tuberculosis. While recovering, he met interesting intellectuals and artists including Carlos Vierra, who photographed and painted all the mission churches in the state. Both Vierra and Meem became key players in an organization dedicated to preserving New Mexico’s mission churches and, in the process, became strong proponents of Santa Fe style architecture.

Pueblo Deco is a style related Pueblo Spanish revivalist architecture. The Kimo Theater in Albuquerque is an excellent example that combines elegant, simplified Art Deco lines with ornament and decoration based on Native American motifs and designs.

Pueblo Deco is a style related Pueblo Spanish revivalist architecture. The Kimo Theater in Albuquerque is an excellent example that combines elegant, simplified Art Deco lines with ornament and decoration based on Native American motifs and designs.

WPA Architectural Projects

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression to provide jobs for people in need. Architects and artisans benefitted from this program and built many fine buildings throughout the state during this time. Public buildings, such as schools, courthouses, city halls and the university, were built as well as public parks, plazas and gardens.

Extraordinary projects funded by the WPA include John Gaw Meem’s buildings at the University of New Mexico and at Highlands University in Las Vegas. Many county courthouses were also built through the WPA. Trost and Trost, architects from El Paso who described their work as “Arid Land Architecture,” built the impressive McKinley County

Extraordinary projects funded by the WPA include John Gaw Meem’s buildings at the University of New Mexico and at Highlands University in Las Vegas. Many county courthouses were also built through the WPA. Trost and Trost, architects from El Paso who described their work as “Arid Land Architecture,” built the impressive McKinley County  courthouse. Their work was inspired by Meem, as well as by Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, who coined the famous phrase “form follows function.” Other courthouses, such as the Curry County Courthouse, were inspired by the linear simplicity and decorative ornamentation of art deco, or “PWA Moderne.”

courthouse. Their work was inspired by Meem, as well as by Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, who coined the famous phrase “form follows function.” Other courthouses, such as the Curry County Courthouse, were inspired by the linear simplicity and decorative ornamentation of art deco, or “PWA Moderne.”

The architect W.C. Kruger leaned more towards the Territorial style in his WPA buildings. Territorial Revival combined the local (flat roofs, earth colored stucco) with the classical (symmetrical buildings with white pedimented lintels and porticos and brick ornamentation) in buildings such as the San Miguel County Courthouse in Las Vegas. The culmination of Kruger’s career came later with Territorial Revival State Capital building, the “Roundhouse,” in Santa Fe.

The architect W.C. Kruger leaned more towards the Territorial style in his WPA buildings. Territorial Revival combined the local (flat roofs, earth colored stucco) with the classical (symmetrical buildings with white pedimented lintels and porticos and brick ornamentation) in buildings such as the San Miguel County Courthouse in Las Vegas. The culmination of Kruger’s career came later with Territorial Revival State Capital building, the “Roundhouse,” in Santa Fe.

Post-War Modernist Architecture

The post-war period and population growth brought influences in from new directions. Modernist buildings based on the “International Style,” emphasized angles and precise wall planes, symmetrical balance, and minimal ornamentation. Simplified rectangles, floor-to-ceiling glass, and an honest use of materials, revealed rather than concealed, were also characteristics of this style. The Simms building in Albuquerque was built in the modernist “International Style,” and it was the first skyscraper built in New Mexico.

The post-war period and population growth brought influences in from new directions. Modernist buildings based on the “International Style,” emphasized angles and precise wall planes, symmetrical balance, and minimal ornamentation. Simplified rectangles, floor-to-ceiling glass, and an honest use of materials, revealed rather than concealed, were also characteristics of this style. The Simms building in Albuquerque was built in the modernist “International Style,” and it was the first skyscraper built in New Mexico.

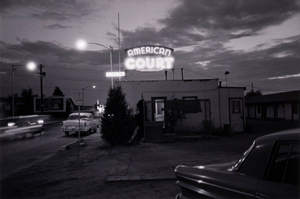

The automobile boom brought the need for an architecture of motels, gas stations and diners by the roadside. This populist architecture incorporated modern buildings, desert decoration, neon signs and advertisements developed to attract motorist from a distance as they drove across the state. Photographers and artists have been inspired by the colorful roadside attractions and buildings that can still be seen when driving on highways across New Mexico such as Route 66.

The automobile boom brought the need for an architecture of motels, gas stations and diners by the roadside. This populist architecture incorporated modern buildings, desert decoration, neon signs and advertisements developed to attract motorist from a distance as they drove across the state. Photographers and artists have been inspired by the colorful roadside attractions and buildings that can still be seen when driving on highways across New Mexico such as Route 66.

Contemporary Architecture

John Gaw Meem’s influence and Santa Fe Style is still a part of contemporary architecture in New Mexico especially in the northern part of the state. However, many different styles of architecture exist in New Mexico today. Postmodernism has meant more freedom for architects to express themselves and to be influenced by a wide variety of styles.

The land, space, sky, light and the history of New Mexico continue to inspire contemporary architects. It is a place for building in experimental ways with alternative earth materials such as straw bale, fired adobes and rammed earth. In addition, the abundance of solar energy in the Southwest, has encouraged architects to create energy-efficient buildings that rely on the sun for heat and electricity. New Mexico architecture is still influenced by its past, but it also looks toward the future with innovative and environmentally conscious, “green” materials and technology.

Antoine Predock is an internationally renowned architect based in Albuquerque. His La Luz residence, on the West Mesa, and Rio Grande Nature Center, in the Bosque, are elegant buildings that blend with and focus on the surrounding landscape. He believes in a “portable regionalism” that he discovered through living and working in New Mexico and now takes with him around the world. For more information> http://www.predock.com/

Antoine Predock is an internationally renowned architect based in Albuquerque. His La Luz residence, on the West Mesa, and Rio Grande Nature Center, in the Bosque, are elegant buildings that blend with and focus on the surrounding landscape. He believes in a “portable regionalism” that he discovered through living and working in New Mexico and now takes with him around the world. For more information> http://www.predock.com/

Michael Reynolds came to Taos, New Mexico, in the 1970s and began to build his “Earthships” from earth and recycled materials, including tires, bottles and aluminum cans. His buildings are designed to be off-the-grid and self-sufficient with solar power, thermal mass, and water harvesting. His building forms are organic and fluid, decorated with colored glass and aluminum. For more information> http://www.earthship.com/

Michael Reynolds came to Taos, New Mexico, in the 1970s and began to build his “Earthships” from earth and recycled materials, including tires, bottles and aluminum cans. His buildings are designed to be off-the-grid and self-sufficient with solar power, thermal mass, and water harvesting. His building forms are organic and fluid, decorated with colored glass and aluminum. For more information> http://www.earthship.com/

Bart Prince is an Albuquerque architect who builds residences through an organic process, synthesizing the client’s needs, the site, the materials and his own ideas. Prince’s buildings are eccentric, eclectic, creative and fun. For more information> http://www.bartprince.com/

Bart Prince is an Albuquerque architect who builds residences through an organic process, synthesizing the client’s needs, the site, the materials and his own ideas. Prince’s buildings are eccentric, eclectic, creative and fun. For more information> http://www.bartprince.com/

Santa Fe architect Ed Mazria strongly believes it is important to lower the carbon footprint of architecture. His glass building at the Biopark, in Albuquerque, is an enclosed plant ecosystem that consumes very little energy to function, yet creates a year-round sustaining climate. His Architecture 2030 initiative focuses on making all architecture carbon neutral by the year 2030. For more information> http://www.mazria.com/

Santa Fe architect Ed Mazria strongly believes it is important to lower the carbon footprint of architecture. His glass building at the Biopark, in Albuquerque, is an enclosed plant ecosystem that consumes very little energy to function, yet creates a year-round sustaining climate. His Architecture 2030 initiative focuses on making all architecture carbon neutral by the year 2030. For more information> http://www.mazria.com/