New Mexico lies at the intersection of four geologic provinces: the Colorado Plateau, the Rocky Mountains, the Great Plains, and the Basin and Range Province. These regions have their own boundaries, and they exert great influence over how the inhabitants of New Mexico have lived. About one million years ago the area attained the character it retains today. Glaciers that had carved valleys and lakes that had flooded basin floors, disappeared, leaving behind alluvial fans, layers of silt, and rock terraces. Once wet and verdant, New Mexico had become a desert. This was what the first human beings who came there found, around 10,000 B.C.

From the perspective of stable human communities, New Mexico is a very dry land. In this region, water is a scarce and precious resource; this was the case with the ancestral peoples who inhabited the area, and it is still the case in the twenty-first century. Water is, perhaps, the single most important factor in the development of any human settlement, and in New Mexico there are only six moderately dependable rivers. Human beings can only survive about ten days without water; without some reliable access to water, none of the other factors on which life depends can be made use of.

For this reason, water in New Mexico has formed the underlying basis of all human activity, and its abundance or scarcity is of the utmost importance for all that happens in the state. Consequently, from prehistoric times forward, water in New Mexico has been subject to an unbroken lineage of formal organizational control.

Indigenous Water Use: Prehistory to Spanish Contact

New Mexico has the longest continuously traceable history of human water use in the United States. Although we probably will never understand the specific origins of irrigation and flood-control practices in North America, we do know that the organized manipulation of water resources in New Mexico spans back to at least 800 A.D. and the run-off collection systems of the Ancestral Pueblo people of the Four Corners region. By 1400, their descendants, the Pueblo people who still make New Mexico their home, had created a complete system of gravity-fed irrigations ditches on the major rivers and tributaries within the state. These early irrigation systems arose simultaneously with the development of agriculture, thus making permanent settlements a possibility in an arid land and leading to the flowering of a rich Pueblo culture.

New Mexico has the longest continuously traceable history of human water use in the United States. Although we probably will never understand the specific origins of irrigation and flood-control practices in North America, we do know that the organized manipulation of water resources in New Mexico spans back to at least 800 A.D. and the run-off collection systems of the Ancestral Pueblo people of the Four Corners region. By 1400, their descendants, the Pueblo people who still make New Mexico their home, had created a complete system of gravity-fed irrigations ditches on the major rivers and tributaries within the state. These early irrigation systems arose simultaneously with the development of agriculture, thus making permanent settlements a possibility in an arid land and leading to the flowering of a rich Pueblo culture.

By the time that the Spanish explorers arrived in the 1540’s, both the Pueblo and Navajo people had developed irrigation practices that depended on centralized authority and mandatory community responsibility for the maintenance of the irrigation canals and ditches. Over the centuries, the Indigenous peoples of New Mexico had achieved an intimate adaptation to their physical environment. The Pueblo people, in particular, became master farmers able to produce “bumper crops” of corn, beans, and squash. These staple crops provided the basis of their existence.

Hispanic Water Use, 1600 – 1848

When the first Spanish settlers arrived in New Mexico in the mid-sixteenth century, many noted the similarities between the irrigation practices of the Indigenous people they encountered and the irrigation systems they remembered from their native Spain. Spanish explorers were likely to have shared a considerable understanding of the importance of irrigation. Like New Mexico, Spain is a largely arid place. For over a millennium the people living on the Iberian Peninsula had engaged in a continuous struggle to gain access to and maintain a sufficient amount of water for agriculture and domestic use. This led to centralized, community based irrigation practices, not unlike that of the Native peoples of New Mexico. Like the Pueblos and the Navajos, the Spanish recognized the primacy of community rights to water resources, and they operated a system of mandatory community responsibility for canal and ditch maintenance.

If the traditional water-control practices of the Spanish settlers and the Indigenous people resembled one another, there was one thing that the Spaniards brought with them that the Indigenous peoples did not have: a body of formal, written water law. This one fact would go far in helping to create in New Mexico a unique legal culture related to the use of water. This heritage of Spanish law was, in fact, an amalgam of ancient Roman and Islamic law, a legacy of the Iberian-Moorish culture of sixteenth century Spain. Essentially, of course, the law became one of the many weapons used by the Spanish settlers to assert dominance over the Native people. But culture does not always respect power, and Indigenous water use practices eventually became a permanent feature of Spanish and later Mexican water customs. The resulting system of community-based networks of irrigation ditches, or acequias, would remain unchallenged until the arrival of the American government in 1848.

In the early Spanish settlements, the residents usually lived clustered together in towns surrounded by cultivated fields and pasture land. Most families depended on their small, irrigated tracts of land to supply them with the necessities of life. For most communities, the irrigation system was so important it was begun even before the houses, public buildings, and churches were finished. Before the acequias were constructed, settlers had to carry heavy buckets of water hanging from yokes across their shoulders.

The success of these early settlements depended on the careful allocation of scarce water resources equitably among the colonists’ tracts of land. Tight community control over the distribution and use of the available water supply was necessary to ensure survival.

In this setting, two types of acequia, or ditch, management systems developed. The first functioned as part of a legally formed municipality or an Indian pueblo. The acequia madre was regarded as public property and its management was the responsibility of the municipal government. Early government instructions for the new town of Santa Fe in 1610, for example, gave the municipal council the power not only to distribute lands but also to apportion water for irrigation.

Another type of management system was formed in communities that had limited or no legal status and lacked a town government. The majority of colonists lived in small rural communities of this type. Under this system, the community ditches were voluntarily developed by interested water users. The distribution of water was strictly regulated by an elected ditch boss, or mayordomo.

Another type of management system was formed in communities that had limited or no legal status and lacked a town government. The majority of colonists lived in small rural communities of this type. Under this system, the community ditches were voluntarily developed by interested water users. The distribution of water was strictly regulated by an elected ditch boss, or mayordomo.

By 1700, an estimated 60 acequias, or ditches, were operating in New Mexico, followed by more than 100 ditches during the next century. At least 300 additional acequias were built in the 1800s. Working without the help of surveying instruments or modern machinery, the construction of these acequias required enormous physical labor. The ditches were dug with wooden spades and shaped with knives. Dirt was removed on rawhides drawn by oxen or suspended from poles carried by workers. The acequias were engineered to take advantage of gravity flow by diverting water upstream from the fields and digging the ditches around trees, large boulders and hills. This type of construction resulted in the serpentine characteristics that are common to many acequias.

Laws

Spanish law established the general principles under which irrigation was regulated in New Mexico. Government documents from Spain stated that all waters in the New World should be common to all inhabitants; that viceroys and other officials should supervise irrigable lands and protect them from livestock; that water should be distributed to colonists on the advice of municipal councils; and that local provisions regarding water distribution should promote the public welfare.

During the Mexican period of government, a series of water laws, based on existing practices, added specific penalties for various violations. For example, a person taking a bath in or otherwise polluting a public spring or well reserved for household uses would pay a fine.

When New Mexico became a territory, it continued to pass laws governing acequias. In 1851, the legislature protected acequias by prohibiting the disturbance of their sources. In 1866, the government ordered that deteriorating ditches be re-established. Acequias were recognized as community organizations in 1895, when the territorial legislature declared them public involuntary quasi-corporations with the power to sue or be sued.

Today, state statutes describe and govern many aspects of the nature, management and operation of community ditches and acequias, much as they did in the earlier years. Those statutes are found primarily in Article 2, Chapter 73, of the New Mexico statutes.

The United States’ victory in the Mexican-American War was formally recognized in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. This treaty, along with the peoples who wished to remain in the area, gave full retention of all property held prior to the unwritten “amalgam of Spanish and Indian (water) law and custom,” a first step toward mixing the “amalgam” with existing American law and custom. Thereafter, the new admixture was well on its way to becoming the law of the land, forming the basis on which the often-bitter fights about water use in New Mexico would be waged.

The annexation of the area now comprising New Mexico by the United States wrought changes every bit as revolutionary as those that came with the initial Native-Spanish contacts in the sixteenth century. American water law, which had been based largely on modified English Common Law practices, was developed east of the Mississippi River, where large amounts of rainfall virtually guaranteed an abundant water supply. East of the ninety-eighth meridian, agriculture could usually rely on adequate rainfall to insure sufficient crops. However, the area that the United States annexed as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was largely arid, with few perennial rivers and very little rainfall. Any agriculture developed in this region would have to rely on irrigation, a system unfamiliar to many Americans.

American political and social traditions further complicated the process. The American ideal of land distribution was deeply rooted in the belief of the sanctity of private property. This ideal celebrated the individual, independent farm and his family who cultivated the land on which they held legal ownership. At its basis, it reflected the assumption that abundant rainfall would support such independence. The belief in representative democracy as the supreme form of political organization was intimately related to this ideal. According to this perspective, independent farmers, owning their own land and free from economic servitude, voted for those leaders who they felt best represented their interests. The two credos of the United States, private property and republican democracy, deeply colored the view of those Americans who came to dominate the arid Southwest.

Not surprisingly, many public figures who lent their voice to the national dialogue about the future of the newly annexed lands expressed deep concern about the lack of water in the region. To their minds, abundant water made possible the ideal of agricultural independence. This, in turn, was the necessary condition for maintenance of a representative democracy. Fearing a loss of democratic independence, many American leaders would have agreed with the army engineer William H. Emory that any system of irrigation “involves a degree of subordination, and absolute obedience to a chief, repugnant to the habits of our people.”

But gradually the allure of potential wealth and new avenues to political power overcame this initial doubt. Thus began the long process of compromise, accommodation, and assimilation that was needed to produce a body of water policy suited to both the land and its many varied cultures. But the spirit of reluctant compromise did not completely erase the racial bigotries inherent in American culture. If white Americans in New Mexico found it necessary to incorporate aspects of the acequia system into their approach to water, they would change it to suit their worldview. One aspect of the acequia system that many white American leaders found offensive concerned the mayordomo. The mayordomo served as both local administrator and as a sort of water sheriff, whose duties included distributing water and commanding the mandatory labor of community inhabitants. To people raised on the rhetoric of independence and individualism, the mayordomo represented the worst aspects of a social system in which a few rich land owners lorded over an ignorant, dark-skinned peasantry. In 1895, the New Mexico territorial legislature dealt the traditional role of the mayordomo a deathblow by transferring his powers to ditch commissioners – a nod in the direction of science and efficiency. By the turn of the century, the entire acequia system would come under attack.

Water policy in the arid Southwest – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah—was largely shaped by the local economics particular to each place. Colorado, for example, had developed a complex body of water law in an attempt to reconcile domestic water consumption with the competing demands of the mining, livestock, and agricultural industries. Each state had to account for interstate use of shared waterways, but in general they could pursue independent water use policies. However, in the case of New Mexico, an independent policy could not be established. The reason lay with the fact that New Mexico’ largest rivers were not her own. The San Juan and the Canadian Rivers are shared with states to the north, east, and west. The Rio Grande is shared with both Colorado and the Republic of Mexico. The Gila River runs from New Mexico to Arizona, and the Pecos River flows into Texas. Thus all major decisions to be made by New Mexicans concerning their water would eventually have to accommodate the claims of competing rivals. This would be an issue that would effectively constrain New Mexico’s use of water well into the 21st century.

National Reclamation Act of 1902 (NRA)

The passage of the National Reclamation Act was a major turning point in the development of the western United States, as it fully opened the spigot of federal spending in pursuit of land development. The act created a federal agency with the power to survey, fund, and construct irrigation, water-storage, flood-control, and soil-conservation projects in the western United States. The overarching purpose of the NRA was to use federal funds to “reclaim” arid lands that were presumed useless without the development of water resources, ideally for the use of small landowners.

The first major project in the state to be seriously considered was Elephant Butte Dam and Reservoir on the Rio Grande, which entered the planning stage in 1905. This project not only catered to the large agricultural and livestock concerns in the southern part of the state, it also looked to facilitate water-appropriation agreements with Texas and the Republic of Mexico.

In 1905, territorial lawmakers formally responded to the NRA by passing a number of laws designed to ensure that New Mexico would fit all criteria necessary to meet “modern” standards and gain the much-needed federal dollars. First, the legislature passed the territory’s first comprehensive water code. This declared that “all natural waters” within the territory’s boundaries would be public property with universal access granted for beneficial use and designated the entire territory a “right-of-way” for “canals, acequias, and other water works. Second, the code of 1905 also created the Office of Territorial Engineer headed by an appointee of the territorial governor and guided by a six-member Board of Control, who were also appointees of the governor.

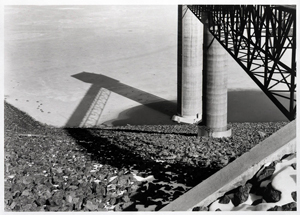

The Elephant Butte project, a three-hundred-foot-high concrete dam, with a reservoir capable of storing over two million acre-feet of water, would provide sufficient water for all downstream users, year round. The building of the Elephant Butte Project began a new era in New Mexico and the United States at large, one that would characterize national attitudes toward the conservation and management of water resources during the entire twentieth century. The days of private irrigation projects and the land monopolies that they had fostered were over. The United States government now considered the conservation and development of water resources a national responsibility. This major shift paved the way for the development of a comprehensive body of federal water law. It also meant that New Mexico now had a major financial resource from which to draw for future economic development. The next generation of New Mexico’s elected officials understood this, and they planned to take full advantage the opportunities that federal reclamation might provide.

The Elephant Butte project, a three-hundred-foot-high concrete dam, with a reservoir capable of storing over two million acre-feet of water, would provide sufficient water for all downstream users, year round. The building of the Elephant Butte Project began a new era in New Mexico and the United States at large, one that would characterize national attitudes toward the conservation and management of water resources during the entire twentieth century. The days of private irrigation projects and the land monopolies that they had fostered were over. The United States government now considered the conservation and development of water resources a national responsibility. This major shift paved the way for the development of a comprehensive body of federal water law. It also meant that New Mexico now had a major financial resource from which to draw for future economic development. The next generation of New Mexico’s elected officials understood this, and they planned to take full advantage the opportunities that federal reclamation might provide.

Another type of project conceived during the New Deal was the San Juan Trans-Mountain Diversion Project. Born out of the Colorado River Compact, the San Juan Project proved to be the most controversial, most disputed, and most difficult ever developed in New Mexico. The San Juan River runs southwesterly down the Continental Divide from southern Colorado and cuts through the northwestern corner of New Mexico. The surrounding mountains feed the river through tributaries that drain an area of about 8,000 square miles. The central aim of the San Juan Project was to divert water from the Turkey Creek tributary of the San Juan into a series of five reservoirs with respective capacities of 15,000; 50,000; 70,000; 290,000; and 500,000 acre-feet, all to be located north of Pagosa Springs, Colorado. In the end, these waters would be diverted to the Chama River in New Mexico, where they would meet the Rio Grande in the Estancia Valley. The final project was not completed until the 1960's after enduring a tortured thirty-year history.

The Conchas Dam Project

The Canadian River has its origins in the melting snows of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of southern Colorado. Winding down mountain slopes, the Canadian carves a one-thousand-foot gorge in the Las Vegas Plateau before spilling onto the Pecos-Canadian Plain in northeastern New Mexico. Northwest of the river stand the red wall of the Canadian Escarpment. To the east sprawls the Great Plains. Passing through New Mexico, the Canadian River cuts through Texas to Oklahoma, where it runs into the Arkansas River. The Canadian River is the largest tributary of the Arkansas River, and controlling it had been the desire of Americans who settled the area since the first years of the twentieth century.

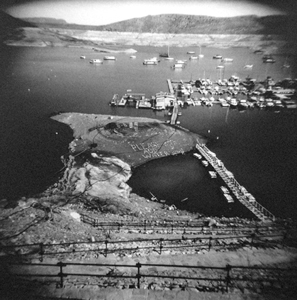

The dream was finally realized in the Conchas Dam Project. Built between 1935 and 1943, the project ended a forty-year effort to develop large-scale irrigation for the region. The quest for a dam on the Canadian River consumed the lives of many dedicated individuals and cost millions of dollars. Fittingly, the project was massive in scale, all the more so because of its remote location. Conchas Dam spans the South Canadian River, a quarter mile below its confluence with the Conchas River in San Miguel County.

Constructed of twenty-seven steel-reinforced monoliths, the grey dam is an Art Deco-style concrete mammoth, rising to a height of 235 feet. At 1,250 feet in length, the Conchas Dam spans the entire river canyon.

The reservoir created by the dam has an 800,000 acre-feet capacity, and it covers an area of about twenty-six square miles. The reservoir extends up the Conchas River Valley about nine miles, and up the Canadian River Valley about fourteen miles. Over one hundred miles of irrigation canals extend the project southeast across the surface of the land. Underground are over six miles of tunnels and three miles of siphons.

The Conchas Dam Project provides an interesting study in New Deal culture. The project brought together several strands of New Deal thought and action, and resulted in a project of great utility and beauty. While possessing a long history, the project was eventually developed under the Emergency Relief Act of 1935, for the purpose of “water conservation, trans-mountain water diversion and irrigation, and reclamation.” (H.J. Res. 117, Pub. Res. No. 11, Statutes At Large 49, Part I, 1935). Approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on July 29, 1935, the Conchas Dam Project became a part of the Works Relief Program, under the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935. Congress authorized funding for the project in the Flood Control Act of 1936. The original purposes of the project were to develop effective flood control for the South Canadian and Conchas rivers, to supply reliable irrigation waters to the area, and to develop electrical power. The project was placed under the jurisdiction of the War Department. Captain Hans Kramer of the Army Corps of Engineers oversaw the design and construction.

Like all large-scale water control projects in New Mexico during the 1930s, the Conchas Dam Project was important because it served as a vehicle for economic and social transformation. During the 1930s, efforts to control water emerged as the only type of projects that could sustain large influxes of federal money into New Mexico. Unlike schools or highways, dams not only took years to develop and build, they also employed hundreds, even thousands, of individuals and consumed massive amounts of supplies. The Conchas Dam was built at a cost of $12 million, an incredible sum that transformed a poor, isolated area into a regional agricultural hub. But it was more than that. The construction of the project exposed many New Mexicans to new experiences and presented opportunities to acquire new skills. Thus, the project helped to develop the state’s workforce. And like all of New Mexico’s large water projects in the 1930s, the Conchas Dam Project helped transform the state from a remote, largely rural society, to a modern urban society.

With the completion of the Conchas project, John Martin Dam at Caddoa, Colorado, became the new focal point of District activity. Tucumcari District personnel transferred to Caddoa and on December 4, 1939, the organizational name was officially changed to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Caddoa District Work proceeded there until the dam was 85 percent complete. With the world at war, however, John Martin Dam was temporarily put on hold.

Soon after the onset of World War II, in early 1942, the District headquarters was transferred to Albuquerque and given its permanent name along with an additional mission. Switching from civil works projects to wartime activities, and with a peak workforce of 3,039 people, the Albuquerque District performed real estate and construction services in support of various military projects in the region. Among those projects was the work at Los Alamos Laboratory where scientists labored in development of atomic energy and its application to weapons.

After the war, the District resumed civil works construction and completed John Martin Reservoir. Other major projects followed in the ensuing years. They are, in chronological order: Jemez Canyon Dam, Abiquiu Dam, Two Rivers Dam, Cochiti Dam, Trinidad Dam (in Colorado), and Santa Rosa Dam.

After the war, the District resumed civil works construction and completed John Martin Reservoir. Other major projects followed in the ensuing years. They are, in chronological order: Jemez Canyon Dam, Abiquiu Dam, Two Rivers Dam, Cochiti Dam, Trinidad Dam (in Colorado), and Santa Rosa Dam.

Today, the District continues several regional civil works projects. In addition, it now provides extensive design and construction services to three New Mexico military bases: Kirtland Air Force Base (Albuquerque), Holloman Air Force Base (Alamogordo) and Cannon Air Force Base (Clovis).

Brantley Dam of the Carlsbad Project

The settlement of the American West has long been linked to the availability of water. In eastern New Mexico, early irrigation attempts focused on the Pecos River. Extensive private ventures in the area, for all their good intent, eventually met failure. Like many irrigation projects across the West, the Carlsbad Project was resurrected by the Bureau of Reclamation. Carlsbad was one of the earliest Reclamation projects, and is one of the more significant projects in terms of surviving examples of mixed 19th- and 20th-century technology.

The Carlsbad Project is located along the Pecos River in southeastern New Mexico near the city of Carlsbad. Located in the Chihuahuan Desert, the project enjoys a number of sun-drenched days during the 212-day growing season. Temperatures sometimes reach 111 degrees at the project’s 3,100 foot elevation. Rainfall of only 12.4 inches a year forced settlers to rely on irrigation methods.

The project’s water supply derives from two river basins. The Pecos River Basin above Lake McMillan drains 16,990 square miles with annual runoff of 234,700 acre-feet. Part of the project’s water comes from diversion of the Black River, 15 miles southeast of Carlsbad, and three miles northwest of Malaga. The river basin above the diversion point drains 343 square miles generating 9,000 acre-feet.

The project included four dam sites and reservoirs, and an extensive lateral and canal network. Avalon Dam and Reservoir are located five miles north of Carlsbad on the Pecos River. McMillan Dam was breached following construction of Brantley Dam, in 1987. It was located nine miles above Avalon, and 14 miles northwest of Carlsbad. Both Avalon and McMillans represented early private irrigation ventures rehabilitated by Reclamation.

The Carlsbad Irrigation District includes 25,000 acres of irrigable land. These lands extend for 20 miles along the Pecos River, three to five miles in width. The project’s irrigation system serves more than 700 persons on 155 farms.

Most of the irrigated lands of the project lie between Avalon Dam on the north, and the mouth of the Black River near Malaga. Stretching north along the project at its inception were the towns of Malaga, Loving, Otis, Phoenix, Carlsbad, Avalon, and Lakewood, at Lake McMillan.

Native American Water Issues

The Native American Water Resources Program, created by the Governor in 1995, is aimed at promoting a spirit of coordination, communication, and good will between Tribal and State governments as separate sovereignties. Under Governor Bill Richardson’s administration, a statement of policy and process was signed with the 19 New Mexico Pueblos to work in good faith to amicably and fairly resolve issues and differences in a government-to-government relationship. This policy and process also extends to other Tribes and Nations within New Mexico.

Rights to water on Indian grant lands and reservations in New Mexico fall within one or a combination of three different doctrines: pueblo historic use water rights, federal reserve water rights, or water rights established under the laws of the State of New Mexico. Water rights administration, litigation and negotiation leading to a settlement of rights to water are exceedingly complex when Native American water rights are involved.

Navajo Nation Settlement

The State of New Mexico and the Navajo Nation on April 19, 2005, signed a water rights settlement that would resolve the claims of the Navajo Nation for the use of waters of the San Juan River Basin in northwestern New Mexico.

The settlement agreement is intended to adjudicate the Navajo Nation’s water rights and provide associated water development projects for the benefit of the Navajo Nation in exchange for a release of claims to water that could potentially displace existing non-Navajo water users in the basin and seriously impact the local economy.

The settlement agreement would establish the water rights of the Navajo Nation in the San Juan Basin in New Mexico. It would draw to a close more than 20 years of efforts to adjudicate the Navajo Nation’s water right owners, it would protect existing uses of water, it would allow for future growth, and it would do so within the amount of water apportioned to New Mexico by the Colorado River Compacts.

The Aamodt Issue

The Aamodt adjudication of the Nambe-Pojoaque-Tesuque stream system (N-P-T Basin)

Is one of the longest running federal cases in the United States. Negotiations to settle the case have resulted in the development of a revised Settlement Agreement. After the original proposed Settlement Agreement was released and presented in public meetings in 2004, representatives of non-Pueblo water users who had raised concerns about the proposed Settlement Agreement were brought into the mediation group so that their input could be better incorporated into the negotiations. Continued negotiations were designed to address concerns and objections of non-Pueblo water users. These negotiations have resulted in the formulation of the revised Settlement Agreement.

Through the mechanisms outlined in the Settlement Agreement, the parties seek to lessen impacts to the aquifer over time while providing reliability of supply and greater certainty regarding use of water in a chronically water-short basin.

Taos Pueblo Draft Water Rights Settlement Agreement

The Taos Pueblo Draft Water Rights Settlement Agreement has been developed through multi-party negotiations among the Taos Pueblo, the State of New Mexico, the Taos Valley Acequia Association, the Town of Taos, El Prado Water and Sanitation District, and the 12 Taos-area Mutual Domestic Water Consumer Associations. Collectively the parties to the Draft Settlement Agreement (DSA) represent the vast majority of water users in the Taos Valley. The United States is also an important party to these negotiations. In negotiations started in 1989 by an acequia-Pueblo Initiative, these seven parties have pursued a settlement of Taos Pueblo’s water rights claims to the Rio Hondo and Rio Pueblo de Taos. Since August 2003, the parties have worked closely with a mediator to complete a settlement. This process has produced the DSA that was publicly released March 31, 2006.

The joint public release is an important step toward completing a water rights settlement in the Taos Valley. While no party has yet approved the DSA, the document represents the agreement reached at the table by the local negotiators. The six local parties (that is all parties except the United States), must now review and approve the document for the process to continue. Once the DSA is agreed upon at the local level, federal negotiations will continue to develop appropriate congressional legislation that approves and funds a final agreement. The negotiating parties will pursue similar legislation at the state level.

Acknowledgments

Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place

David Stuart

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2000

Supplying Water and Saving the environment for Six Billion People: Proceedings from Selected Sessions from the 1990 ASCE Convention

Udai, P. Singh, and Otto J. Helwig, Editors

New York: American Society of Civil Engineers, 1990

"Dividing New Mexico’s Waters, 1700 – 1912"

John O. Baxter

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1997

Dennis Chavez and the Politics of Water, 1931 – 1941

Christopher J. Vigil

Master’s Thesis

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2006

Acequias

New Mexico State Engineer Office, Santa Fe, NM

Water in New Mexico: A History of Its Management and Use

Ira G. Clark

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1978

Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and Growth of the American West

Donald Worster

Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985

Acts of the Legislative Assembly of New Mexico, Thirty-sixth Session

New Mexican Printing Co., Santa Fe, 1905

“Correlation of the Model and Prototype Tests of the Conchas Dam Service Spillway and Stilling Basin”

Geary M. Allen, Jr.

Master’s Thesis,

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, 1952

United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation,

Regional Director, Region 5.

Factual Data-Carlsbad Project, 196?

The Bill Lane Center for the American West

http://west.stanford.edu/

http://exploringthewest.stanford.edu/